The Copping Diary

A Glimpse Into the Past

The Journal you are about to read was written during a ten year period from 1836 to 1846. Many years later, a typed copy was made and Beverly Prud’homme put it on a diskette which has been posted on this site. George’s earlier journals were destroyed when the Copping family lost everything in a fire, including his books, diaries and presumably their linens and furniture, almost everything that they brought from England. The journals for 1839, 1841, 1842 and any written in the four years prior to his death are missing. Miss Mabel Mitchell, a Copping great grandchild, who created a Tree of Copping Descendants in1904, may have played a part in the salvation of the remaining diaries. It is unclear if the original journal is still extant. We would be grateful for any information concerning its fate.

The Journal records the daily events of George Copping, his family and their interaction with their neighbours after settling at Rawdon some time between the fall of 1821 and September of 1823. It naturally focuses on his own family and his nearest neighbours who were the Browns, Marlins, Laws, Petries and Asbils. Other families who were near and often mentioned include the Hobbs, Dunns, Reids and Boyces but many others are also named.

George lived for a time in the Quebec City region where they had arrived and two more children were born.

Four years later they continued up the St. Lawrence to Montreal and while resident there, three children were born. Then, the final move to Rawdonin the the fall of September of 1821. It was here in the Church of England and Ireland that the youngest two children were baptized.

When the Journal opens, January 1st, 1836, George Copping was settled on lot 26 of Range 6, that became know as St. Alphonse Road.

The five oldest offspring were married or living in their own places, the six youngest children still at home with their parents. The family was living in the new house, as yet unfinished, built to replace the original cabin that had been destroyed by fire.

This new house is still standing and lovingly being renovated after many years of neglect and wilful damage.

The Coppings were hard working, good and intelligent people. Exactly the kind of immigrants authorities hoped to attract, and have settle in Canada. George Copping appears to have been a much-respected and trusted member of his community and was often called upon to mediate in disputes between neighbours.

Wandering sheep, pigs, cattle and horses caused a great deal of loss and damage to crops and so keeping fences mended was a constant pre-occupation for George. The old adage “Good fences make good neighbours” was constantly tried. From early spring until late fall, keeping their animals in and their neighbours’ animals out was a hard fought battle with many skirmishes lost. This caused no little amount of hard feelings and George was often called for ‘consultations’, as he referred to them, to settle damages. This required several community members to arbitrate, assessing damages and recommending retribution. Occasionally he had harsh words for those whose lack of fences or exaggerated demands for retribution caused problems among the neighbours.

George served as a trustee of the school and as a member of the board for the Church of England. He was an advocate for schooling and when the boys were in their teens, long past the age of regular schooling for working folk of that time, they sometimes attended night school. At one point George mentions that Thomas, who is 20 years old, is at school because his finger is too sore and he is unable to work. For many people at that time school was not an option.

As many of the settlers were illiterate or not comfortable writing letters, George would be called upon to assist when they received a letter or wanted to send a written message. Because of their literacy, the Coppings attracted neighbours who came to borrow books or procure paper and ink.

It is shocking to read how often men and especially the young men were seriously injured or killed while using axes, scythes or by falling trees. There are frequent references to rabid dogs, bears, wild cats, smallpox, measles, whooping cough, toothaches, fever, arthritic joints and bad backs. You had to be tough as nails to survive in Canada in those days because it was survival of the fittest for animals and people.

The loss of children was as deeply felt then as it is today and although the loss of a child was an emotional trauma, it was the loss of a helping hand in its youth and an expected asset for the parents’ old age. Parents were forced to rely on their children when they could no longer function independently as homes for seniors and pensions were not known.

Few couples successfully raised to adulthood all the children born to them. The Copping family was an exception in that every one of their eleven children not only survived but also all lived to a good old age. Nine died in their seventies and eighties, one in her late sixties and Charles’ date of death is not known.

The death of a working adult and the loss of crops or beasts could mean the difference between life and starvation but were anticipated due to disease and accidents. The lack of a social safety net meant that the community was obliged to furnish from their own meager supplies for the less fortunate. Neighbours contributed and collected for those who had fallen on hard times. The Journal records George’s contributions to these collections. He also writes of neighbours taking refuge at his home during times of stress until other arrangements were made.

The people of the settlement were interdependent because the skills and trades of the community were needed in order for the whole to survive and live well. The blacksmith, miller, store owner, tanner and lumber mill owner were all extremely important members of their society.

The Copping homestead was a gathering place; neighbours used their potash plant and their barn for threshing of grain. George’s sons regularly delivered potash and sometimes wooden lath for building to Montreal. It was not unusual to deliver goods for a neighbour as well as their own produce. The Coppings produced pearlash, a purified form of potash, used in the production of finer soaps and in glass making.

The Coppings made repairs to their own carts, wagons and sleighs, as well as doing barrel repairs and making furniture etc. All family members planted, weeded, cultivated and harvested crops of all types for their own use and for barter or sale.

Elizabeth did nursing and midwifery for the family as well as for community members. She was often away for days at a time when someone was giving birth, was ill or suffered a severe injury. Doubtless, when a case ended in death, Elizabeth would be pressed to stay on to comfort the family and assist with laying out of the body.

Despite seeming to be very capable in many ways, Elizabeth did not do the family tailoring. This was done by a neighbour, often Mrs. Petrie or Mrs. Brown, in exchange for work done by “the Boys” or Mary. They came over to measure and cut the required item and then took it off home to sew, coming back for further fittings as needed. Interestingly, both men and women chose and brought home yard goods for pants and jacket making and on at least one occasion a son cobbled his own moccasins from leather he got from the community’s leather tanner.

Elizabeth and her daughters worked long hours at farm chores and gardening as well taking care of the large household – washing, cooking, sewing and cleaning, all done by hand. These regular household duties are rarely mentioned, possibly because they were not income producing but more likely, because they were part of routine and not worthy of note just as he does not mention his own repetitive chores.

As well as household duties, the women worked in the fields and gardens without regard to their gender. As early as the age of eleven, the girls planted, seeded, weeded and hoed. They pulled weeds and cut thistles. They reaped, bundled and hauled in the hay and grain. Neither were they excused from the dirty, backbreaking task of digging potatoes and hauling them in to the root cellar. Apparently neither long skirts nor fourteen pounds of clothing hampered the women’s work. At sugaring time, they were in the bush to gather and boil sap and to help with the potash letching when needed. No delicate ladies, these!

Frequent overnight guests must have added considerably to their work. George often mentions that people passing by were bedded down for the night as they paused in their journey to and from Montreal. As well, he reports children staying to attend the nearby school.

Although it was only in the most severe weather, or extremely poor road conditions that none of the Copping family attended church, it was rare for all to go at the same time. Sometimes they attended services at different churches, or sometimes at both the Protestant churches. At this time, in addition to the Church of England, to which the Coppings were attached, there appears to have been a Presbyterian congregation as well as visits from itinerant Methodist preachers who eventually established a church in the community.

Church and businesses were meeting places where news was exchanged, as well as to repay and receive payment of debts owed. Arrangements for an exchange of labour or the borrowing equipment or materials were also made when neighbours met.

There were frequent references to sons, daughters, wives and husbands travelling to someone else’s property to borrow or return items, to deliver barter items of payment, perform services or hours of work or come together to help get a big job done. All this travelling back and forth is surprising. A person might assume that people attended to their own work all week and would rarely see others during that time but this is proven totally incorrect as you read through the journals.

George, with few exceptions, wrote daily in his journal. He used the journal to keep a record of debts owed to him and by him. He sometimes repaid debts by barter, as in one instance “over eleven pounds of butter”. He kept meticulous records of how much sap was collected and how much maple sugar was produced. He recorded exactly how much he paid for meat per pound, how much he charged others for meat from his animals and how many pounds his own butchered animals produced for the family’s use. He kept track of planting and harvest dates, the production of his fields, how much wood was cut, firewood split, wooden lath made, furniture built, sleighs, wagons and carts made and loaned along with oxen or horses to pull them, as well as the potash produced. Possibly he wrote down the loan of equipment and tools so he would know where to look for them if they weren’t returned.

It is clear that he is not recording events for a reader or writing a social history. There is no follow up on items of interest to us and supporting evidence is seldom provided. In fact, he would be astonished that we are interested in reading the Journal today. His references to political events (1837 Rebellion), family scandal (Clara leaving her marriage) or murder are oblique and often puzzling and frustrating.

For instance in 1838, there are four entries referring to the murder of a young man surnamed Steven (or Stephen or Stephens).

June 12 – Mr. Dugas, Daniel Truesdell and John Smiley called in here on their way from an inquest on Mr. Stevens, killed by three McDon . . .

June 13 – James has gone to the funeral of the young man Mr. Stephens that was killed the day before yesterday.

June 22 – Thomas has gone to the inquest of poor Mr. Stephen, they took open the coffin and looked at him and they went to Mr. Truesdell’s and established the verdict of willful murder against John and Alexander McDonald.

July 1 – in the afternoon William Eveleigh, John Eveleigh, Mr. Rourke, William Sinclair and the two Stephen’s came to take Edward McDonald and they took James and Henry with them and their muskets and ball cartridges.

Further, on Sept 1, he reports “old John McDonald” is in gaol. Possibly, this is the Jack McDonald who is reported as dying on 15, April 1840.

For George these were important events that were mentioned in his daily input. He leaves us to wonder how the young man was killed, did they really open the coffin nine days after burial, did they actually arrest Edward and why did this take two weeks to occur? Were the accused hanged? We may make a story of it if we wish; however, we cannot be sure we are getting it correctly.

So, read and enjoy these remarkable background glimpses remembering that the full story lies elsewhere.

The Copping Children in the Journal

The descendants of the children of George and Elizabeth Copping are now spread across North America and to many places beyond. The Coppings had a unique approach in the naming of their sons as will be seen in the following description of their lives in 1836 when the Journal commences.

George William

The oldest son, George, was married to Mary Gray and in 1836 they were living with their three little boys on Lot 20 North on the 4th Range. A ticket of location had been issued to the Coppings for this lot in 1824. George Jr. would have been about an hour’s travel from his father’s home farm (6 / N 24), and yet, there was much coming and going between the two places.

The brothers and sisters who were still living at home frequently went “down to George’s” to lend a hand, borrow a piece of equipment, or to join in festivities. His mother, Elizabeth, also went to give a hand in the house or garden or help with a sick child. His sister, Mary, went to spin, baby sit and visit. George’s place was also a stop on the way home from John’s mill in what is now St-Ligouri.

George was appointed as one of the first three “road and bridge inspectors” for the Township of Rawdon on November 13, 1845 along with Antoine Dandurand and John Daly.

William George

The second son, William, and his wife, Margaret Gray, (Peggy) with their first son, were settled at 6 / N 23 next to the family homestead. Margaret was a sister to George’s wife, Mary. They were from a large Irish Protestant family from County Sligo. William and Mary later moved to 8 / S 24, formerly owned by George Keo, but we find this move was not without its trials and tribulations as we read through the Journal. The “Boys” often gave William a hand and they worked the potash together. At times, Old George and even Elizabeth and Mary boiled potash for William as well as for themselves. Joseph, once he passed his thirteenth birthday, which would seem to be the coming of age, frequently hauled and chopped wood, or took grain to the mill for his brother.

William did quite well for himself and there is regular mention in the Journal of Peggy’s maid servant and a cook is mentioned, as well. William became a councillor for the Municipality of Rawdon, and a Justice of the Peace.

Tragedy hits the households of the two eldest sons shortly after the Journal opens. They each lose a son within hours of each other. Both babies are waked at George’s and a procession leaves from there to go to the church for burial.

Charles John

Charles, who would have been about 25 years old at the time of the Journal, did not live in the Rawdon area. He was apprenticed to a leather dealer, Eveleigh in Montreal. Me Married

A look at the 1825 census seems to indicate that George and Elizabeth and all ten children were at Rawdon in 1825. He was apprenticed at a very early age to a friend, John Eveleigh, in Montreal who had a leather trade in Montreal.

Charles later married Emma Bennett of New York State and they had 5 children all born in New York. In the Journal, Old George mentions receiving letters from Charles and sending letters to him. Charles sent him a pair of boots, as well.

John Charles

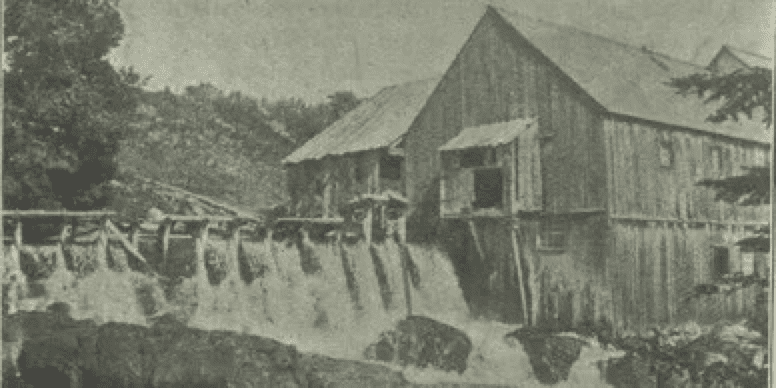

John operated and later owned a flour mill on what was then the first range in Rawdon, now a part of St-Ligouri more than an hour’s ride from the home farm.

Young George’s farm on the 4th Range would have been about halfway from the home farm to John’s.

George mentions going down to John’s for meal and flour. He also refers to James going down to work for John.

Did John actually own the mill at this time and was it part of the family property? It would appear that he was apprenticed to or working for Philomen Dugas, a well-known and successful miller, merchant and entrepreneur.

In support of this idea is a list of students who were attending the School at the Forks, very close to the Dugas establishment, in 1826. John Copping is one of only eight scholars and the only one whose family did not live with a half mile of the school and the only Copping.

In 1837, John married Julie Dugas, Philomen’s daughter; she was another of the students at the School at the Forks in 1826. She, as were her parents, was born in the United States. Although this was a mixed marriage – she had converted to Roman Catholic –there does not seem to have been any alienation between the families.

John converted to the Catholic faith shortly before the marriage and the young Dugas-Coppings were brought Catholic. Admittedly old George seemed a little uptight at first, but things were soon smoothed over. He often went down to the mill and when Julie was having difficulltied in her firdt pregnancy, Elizabeth went down to stay with her.

Julie and John also came up to visit regularly at the homestead.

Clarinda

It is easy to imagine Clarinda being the apple of her father’s eye, and the darling of her big brothers. She was the first girl and remained the only one for another nine years until Elizabeth was born.

Clarinda is said to have been particularly pretty and have had a lovely singing voice. That she was very attractive is evident in photos of her that have survived from later years. Her brother, William, was remembered as an accomplished violinist, and would accompany her. The older folk used to say that on a beautiful evening in spring or summer neighbours would gather for an impromptu concert given by the pair.

When the Journal opens, Clarinda had recently married Edward Reinhardt and they settled on his farm nearby her parents home farm.

James & Thomas Henry

The oldest of the six children still at home, James 22, and Thomas 20, were already looking around for their own sections of land. James was covertly courting his future wife, Florella Wright, in Montreal – it is always James who makes the deliveries of potash to Montreal.

Thomas already seemed to have his eye on a girl from “up the township”, Bessie Sharp, and was also interested in finding his own place. Their search and settling is detailed, as much as George details, in the pages of the Journal.

Henry

Henry, 19 at the time the Journal opens, is the youngest of ‘the boys’ referred to in the daily account. Once his two older brothers were settled he acquired a lot directly behind the homestead. He was also married to the first of his three wives and settled before the end of the Journal. The first two wives bore him 14 children and the third raised them.

Mary, Joseph, Eliza

Then there were the three youngest children – Mary, Joseph and the baby of the family, Eliza. Mary and Joseph as the names imply were a pair, often working together in the fields and garden. At the beginning of 1836 they were about 14 and 12, respectively. Mary had the unenviable position of being the oldest girl at home and as such shouldered much responsibility. She helped out at home, where she had her own crop, calf, pig and sheep to look after and worked in the fields and garden.

She was frequently sent to help aiing neighbours or to her brothers George or William to help in the home or to nurse an injured or sick child.

Eliza was almost ten when the Journal opens and is seldom mentioned except when she is ill or sent on an errand to purchase a an item from a store or deliver a message. It is hard to imagine this ten year old walking alone for several miles on difficult roads diring extreme cod or heat!

It is interesting that while the first son was given his father’s name, it was the last child who was named for her mother.

Eliza also helped with household tasks or even outside chores, but there is little mention of her contributions.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS, PEOPLE AND THEIR TRADES

Heather Craik Moser of Dunrobin, Ontario and Sharon Craik Kenney of Tswassen, British Columbia have written this Glossary of Terms, People and Their Trades. They are sisters, descendants of James Brown (1813-1882) who was granted a ticket of location for the NW 1/2 of lot 25 of the 7th Range in 1826. He was a son of Robert Brown (born 1783 at County Antrim, Ireland, died at Rawdon 1831) and his wife Margaret McMullan (1776-1846). They were the parents of seven children who are each mentioned in the Copping Journal. The Browns appear to have arrived in Canada about 1824 and were settled at Rawdon in the fall of 1825.

Beverly Prud’homme has made additions to the glossary whenever local usage of a term (or custom) differed from that of other communities or the meaning today. Daniel Parkinson has added additional information especially about the settlers named in the journal .

Allen, Mr. – John Allen, was a native of Scotland, a cobbler or shoemaker/repairer. He and his wife arrived in Montreal in 1820 and had a ticket of Location at Rawdon in 1823.

Archambault / Arshambo, Monsieur – Miller

Arshambo / Archambault, Monsieur – Miller. Possibly this is François Archambault who received Letters Patent in 1855.

Awl – Tool for making holes in leather so it can more easily be sewn. Used in cobbling (shoemaking) and harness making.

Barrelmaker – Needed to produce storage containers for foodstuffs etc. Barrels were needed to transport the potash, butter, etc., to Montreal as well. William was the barrel maker in the Copping family.

Bee – It is a calling together of many people to work at a large, heavy task in order to complete the task more quickly. It was hard work, but considered a party and social occasion as well. The person holding the bee provided the food and drink, which was often supplemented by neighbouring women. The men had ploughing, mowing, pulling of stumps, logging and harvesting bees as well as bees for ‘raising’ the walls and roof trusses of buildings. The women might have bees for quilting, and preparing wool or flax for spinning etc. These bees ended in a party with music, song and dance far into the night. Sometimes liquor was present, particularly for the men.

At many places there was a whiskey jar passed around rather frequently among the men as they laboured. The result was sometimes serious accidents, brawls and even murder. As a result, not all settlers approved of them and the more serious-minded considered them the work of the devil because of the evening shenanigans.

Blacksmith – Old Mr. Norrish – He produced nails, bolts, harness parts, axes, scythes, awls, hammers, horseshoes, pots and chains etc. He also shod the horses with the shoes he made in his forge. The Coppings used Mr. Norrish but there were other blacksmiths in the community at this time. (See: Norrish.)

Blistered or blistering – This was an old time remedy for toothache, boils and infection, for people and livestock. Nursing was women’s work, so one of the womenfolk in a house would make a scalding hot poultice of some organic substance such as flour, meal, grain (sometimes even stale bread) and boiling water. In the case of a boil or infection, it would be put into a cloth square and tied in place until it cooled. The heat would help to draw the infection out.

George mentions using such a poultice on the back of his neck to cure toothache! Perhaps the pain of that burned and blistered skin would make you forget your tooth pain. Apparently it was not particularly effective as two days later George is still complaining of a toothache. In the case of colds, chest congestion and coughs, the preferred poultice would contain hot mustard too. This mustard ‘plaster’ was prepared by spreading the boiling hot mixture on a cloth and laying it, mustard side down, on the patient’s chest until it cooled. The heat of the plaster and burn irritation to the skin caused blood to rush to that part of the body and helped to break up the congestion or infection. It sounds painful and dangerous, but it was all they had to combat serious illnesses such as pneumonia and whooping cough etc. It was better to be alive with a burned chest than dead and buried. (See ‘Pitch Plaster’)

Boiling – As in, “He is boiling today”. This refers to boiling the lye solution to remove the water, thereby concentrating and drying it to form the white powder of refined potash. Care had to be taken at all stages of the process before it was dry. Any liquid splashed or spilled on skin would burn it and if some splashed into eyes, it could blind. The resulting powder was then packed in barrels to keep it dry during storage and for easy, safe handling during shipping.

Boiling in reference to the making of maple sugar meant boiling the sap of the maple trees in a large black pot until they reached the consistency required to make sugar. The last sap, which was not good for sugar, was boiled to make vinegar.

Booth, Mr. – Plasterer. This was either John or James Booth; both were natives of County Leitrim and in arrived with their families at Rawdon about 1830. Their relationship to each other is not clear.

Bourne, Rev. R.H – Rowland HillBourne replaced the Reverend C. P. Reid (1834 – 1836) and was the incumbent minister at Christ Church, Anglican from 1837 – 1846. He was a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. He married and was widowed while at Rawdon. In the early days the parish was jointly Church of England and Church of Ireland.

Bow or Ox Bow – this is a wooden collar (single or double) made to yoke an ox or oxen to farm equipment for pulling. A heavy, curved piece goes over the top of the neck and a lighter-weight, steam-bent (bowed) piece extends from the collar, under the neck and up to the collar again. The Ox’s head is locked in with a wooden pin. Chains are attached to a circular ring on the bow and that chain attaches to whatever is to be pulled or drawn by the ox. The French Canadian style of ox-bow went over the animal’s horns instead of his neck. This gave it much less pull power.

A different arrangement (made of wood covered in leather) is made for a horse to

pull something heavy and is naturally called a horse collar.

Breaking Roads – Pushing through the woods with oxen and a weighted sledge or sleigh in order to break the brush and small saplings down. If this was done annually, then the roads remained open and trees could not grow up to clog them. Breaking roads was maintenance to ensure you didn’t have to clear them again one day.

The term used in winter meant slogging through the snow in the bush or on the road with horse or oxen and sleigh to pack and track the road.

Calf – A newborn or young of the bovine family.

Calf Bed – When it ‘comes down’ during or after a heifer or cow gives birth, it means a prolapsed uterus. Unless the uterus is put back in again, the animal will die. This is extremely hard work to accomplish and requires technique, patience and a lot of arm and shoulder strength.

Canadian – Referred only to French-Canadians and not English-speaking people or any others of the time.

Carpenters – The Misters Genenerux (sic. Genereaux?) were father and son. This industrious pair clapboarded George Copping’s house, made door and window frames, and laid floors for him. The first dwelling was usually a rude hut, even, made of rough hewn logs and built hastily to shelter the family the first years. Once the family was established and time allowed for it, a better dwelling was erected and this one would have had wood siding unless it was made of stone. The Copping home was being rebuilt after a fire destroyed their first home.

Genereaux was not issued a Crown Grant at Rawdon and may have been from St-Jacques as George refers to their leaving, being gone, returning, etc.

Chopping – This refers to the very hard work of cutting brush and small saplings to clear land once the trees have been removed Often chopped areas were burned to discourage re-growth of scrub, and encourage the growth of grass for grazing. This grass was often very lush as a result of the fire releasing growth-promoting minerals from the burnt grass and brush. Actually here, chopping meant felling trees which was done with an axe, if you can imagine what a task that was!

Clockman – Mr. Fairbank, a repairer of clocks. There are two references in the Journal the first is on Friday, 6th. April, 1838 . . . “and Mr. Fairbank, the clockman left his horse here tonight” and on Wednesday, 5th Feby, 1840, “The clockman called for the remainder due.”

Beverley Prud’homme has the Copping family clock and it was manufactured by the Twiss family, a father and five sons all in the clock business, who were from Connecticut but were established in Montreal. One brother, Russell lived at St-Jacques and is buried in the Methodist Cemetery at Rawdon. He died on May 14, 1851 in a hunting accident at age 43. Possibly Mr. Fairbank was an employee, the name does not appear in church, census or other contemporary documents. He may have been adjusting the clocks and / or collecting payments.

Clog – George says he made “a clog” for the black horse because they couldn’t keep it in the pasture and out of the crops. A clog is a heavy, short length of log tied in the middle and attached to the horse by a rope. It was intended to make it difficult for an animal to go far and impossible to jump the fences. The animal would be reluctant to drag the log as it would catch in brush, on tree trunks, among rocks and in the rail fencing.

Cooper – Maker of wooden barrels for storage and shipping of goods, both liquid and

solid.

Copping, Elizabeth – (Mrs. George Copping, senior) Nurse/Midwife, farmwife. She was

born on February 10,1782 at Chigwell, Essex and died at Rawdon February 8, 1852.

Cradled Oats – harvested oats that were placed in a crib (cradle) for storage in a barn.

Cut – As in ‘We got the hog cut today’ – The castration of a male animal. A hog is a castrated boar but sometimes hog is used as a generic term for pig. A steer is a castrated bull calf and an ox a fully grown steer used for draught purposes. In the case of a stallion, castration makes it a gelding or gelded horse. Castration renders male animals more docile and thus safer and easier to handle. Steers and castrated hogs gained weight faster and the meat that not as strong-flavoured as that from fully fledged males.

Cutting Potatoes – Cutting potatoes, which have been saved as ‘seed’ [called sets], into pieces which are planted for a new crop in the spring. Each piece of seed potato or set should have at least 3 or more ‘eyes’ in it to ensure a plant results. The ‘eye’ is one of many dimples in the potato surface where a sprout will appear, either before or after planting.

Draw – To draw means to carry, move or convey a load of anything from one place to the other.

Drill, Potato – A drill is a row of earth raised with a horse and plow in which holes were made to plant the potato “eyes. One was making or drilling holes in the row of earth.

Dugas, Mr. – Miller, entrepreneur. He was born in the USA but was probably of Canadian or Acadian origin. He was known as Philémon or Philemon and as Firmin. He was one of the earliest settlers and investors in the Rawdon area. He was also land agent at one point and owned two mills, a sawmill and a gristmill as well as a general store. He was the enumerator for the 1825 and 1831 census and one of the earliest school commissioners. His daughter Julie was married to John Copping.

&c. – Old way of writing etcetera or etc.

Fan – Sieve for winnowing grain from chaff.

Fit – When used in reference to a crop, means fit – ready for harvesting now, or unfit – not ready to be harvested yet.

Flax / Linen Making Terms:

This was considered women’s work, even though it was hard, heavy work. It was women’s work because women were responsible for making clothing and all the processes from start to finish. The fibers were rough, tough and often cut hands and fingers. They must have had impressive biceps and heavily calloused hands in those days! There are several references in the Diary to “the women having very sore hands” from working with the flax.

Stripping – To strip or tear off the outer covering or tough sheath of the flax stems.

Beetling – To beat with a heavy wooden mallet or beetle to release long fibbers from an organic material such as flax stems. This flattens the stems prior to scutching.

Scutching & Hackling – This breaks the flax to release the long strong linen fibers from the beetled or beaten stems. Elizabeth Copping assembled 10 to 12 women to help her with this chore, according to her husband. George Copping spelled it ‘scuthing’, but spelling was notoriously ‘flexible’ in his time and place. Actually, a grammar had not been defined, as yet.

Spinning – A spinning wheel would be used to twist the fibers into a fine thread or yarn. This thread would be used for sewing, to weave into cloth on a loom or less often, it was used to knit the thread or linen yarn to make clothing. Newly woven linen was very picky and scratchy so was often used on beds for sheets for a while before being made into clothing. A few washings helped soften the fabric. Naturally, the spinning wheel was also used to make yarn from sheep’s wool or fleece. If they wanted coloured yarn or thread, rather than the natural cream colour of both wool and linen, vegetable dyes were used to colour both fibers, prior to spinning it into thread or yarn. Most liked to have at least one black sheep in order to produce black yarn for weaving into cloth or for knitting.

Floor – sometimes refers to the clean wooden floor of a barn or outbuilding where grain is flailed or threshed to separate it from the straw prior to being taken to a mill to be ground for flour between granite millstones. It would be known as the threshing floor and would usually be between the two lofts. It was also where the team was driven into the barn to unload the hay or grain.

Grain or Hay Harvesting – The grain is cut down, or reaped with a scythe, racked up and bound (tied) into bundles or sheaves. Sheaves are then stacked together in the field to form a teepee shape, called a stook. The stook is an efficient stacking method because it sheds rain and allows the grain or hay to dry in the sunlight and air before storage. If it were stored wet or even damp it might sour or rot. This would make it unfit for feeding livestock. It was also extremely dangerous at it would heat and cause a fire, burning the barn and possibly the stable, even the house. Salt could be spread on the hay/straw if it was slightly damp, but even that was risky as well as being an added expense.

Gaol – The Old English spelling for jail

Grass seed – In this instance it means hayseed and not the type we use today to make a fine lawn.

Heifer – a female calf or young female which has not yet given birth.

Hobbs, Mr. – Miller. George Hobs or Hobbs, as it was usually spelled, was a Loyalist born in New York State possibly of German origin and came to Rawdon from Prince Edward Island.

Hooey, Mr. – Shoemaker. Possibly John Hoey who received his Letters Patent in 1836.

Jeffries, Col. – Correctly spelled Jefferies. Lt. Colonel John Jefferies owned about 1000 acres on the First and Second Ranges and lived on lot 20 South of the 2nd Range. He was Justice of the Peace at the time of the Diary. He campaigned to have a church built in Rawdon Village to supplement or replace the earlier one on the 2nd range. Old George and “the Boys” supported this project and a wooden structure was built on the corner of Church and Third Avenue facing onto Church Street. This structure was replaced as a church in 1857 by the present stone building.

Keo’s, Mr. – Schoolhouse – It was used as a schoolhouse through the week and on Sundays, it was used for Sunday school which was attended by adults as well as children. This is George Keo or Keogh whose Ticket of Location dates from 1821. He lived at 8th Range, the South half of Lot 24 and was a near neighbour of the Coppings.

Law, Mr. – Henry Law was a neighbour, a native of County Down. Hugh and William Law are also members of this family who were first noted at Rawdon in 1822 and are mentioned in the Diary. Henry was recognized for his knowledge of animal illness and problems and was called to put back the “calf bed” or uterus of a cow which “came down” when giving birth. In the absence of a veterinarian, the settlers depended on the skills of such amateur practitioners. Henry was also called upon to make wooden coffins on one occasion.

Letching Potash – This refers to leaching the lye from the ashes. (See Potash Making Terms).

Lime – Lime is prepared by heating limestone to a high temperature in a kiln so that it disintegrates into a powder. Lime was needed for agricultural purposes and was sprinkled onto fields or garden plots to ‘sweeten’ the soil and promote better plant growth. Lime was also needed to make mortar and plaster. In colonial times it would have been mixed to make a mortar mixture to fill in the spaces or chinks between logs in a log cabin or out building. The interior walls of the houses were finished with lath and plaster. This kept cold and wind out and made the buildings easier to heat with a fireplace or to retain the body heat of animals kept in a stable. This chemical was and is still used today to disinfect animals, their pens, and farm buildings. A hydrated lime mixture (lime and water) kills the germs that cause disease. It is also used to disinfect outhouses. Being able to purchase lime was important for human and animal health. Lime (probably from St Jacques de Montcalm) was used to refine the potash to make pearlash, a higher grade of potash, which fetched a better price on the market.

Meal – Grain, which has been coarsely, crushed (usually corn and oats) for animal and

poultry feed and to make porridge for people. The crushed meal might be sieved to

ensure it was of even texture and without too many larger pieces of grain, which

would take longer to cook and be too hard to chew.

Millers – Hobbs, Dugas, and Archambo (sic. Archambault) are those mentioned. There were others in the community at this time.

Melting – Boiling water and animal fats together to render or clean and purify it. Fat from cattle and sheep was called tallow and fat from pigs as called lard. Once the water boiled and the fat was rendered or melted, the kettle would have been removed from the fire. When the solution cooled, the re-solidified fat could be skimmed off for use in cooking, soap making and candle making. The rendering of animal fat creates an awful stench and was done outside over an open fire.

Melting wood – Firewood types which burn especially hot to burn under a rendering kettle to boil. Melting in the Diary refers to ashes in the making of potash.

Minister – Rev. R. H. Bourne was the Anglican incumbent when most of the remaining diary was written. (See Bourne)

“Moulding” up Potatoes – Mounding or hilling the plants up with earth to encourage rooting from the buried stem, thus producing more tubers. Often, when livestock had gotten into the garden and potato plants, they had to be replanted and hilled or moulded up again, in the hope that they would take root and live on to produce a crop of mature tubers.

Necessary – A polite word for outhouse at the time.

Norrish, Old Mister – Blacksmith. William Norrish, a military pensioner, was a native of Devonshire, England. He was born in 1779 and only a year older than Mr. Copping. He immigrated to Rawdon with his family in 1832. He was also a gunsmith.

Nurse / Midwife – Elizabeth, Mrs. George Copping, senior was called out at all hours of the night or day to attend sick people and births. George carefully recorded when his wife was away helping people. It seems reasonable that she would receive some recompense for her assistance although this is not known. Neighbours would not want to “impose” or “be beholden” and would find a way to thank her for her kindness and assistance.

Peas – Likely refers to peas as well as all types of beans. Interesting to note that Mr. Copping seems to have prized ‘Mrs. Allen peas’. Each person would save seeds and people would vie for any extras of a variety deemed to grow or store better, have special properties or a better flavour. Understandably, such seeds would come to carry the name of the person who originally shared them with other people in the community. These names were used to describe which type of pea or bean had been planted, harvested, stored for eating and saved for next year’s seed.

Pitch Plaster – George mentions getting a pitch plaster from someone to help his sore shoulder. It would seem that plasters were made from pitch too. Pitch is the sap or resin exuded by trees and usually refers to that from evergreens such as pine or spruce. The a fuller account of plasters).

Plane – As in, “James took a plane up to his place”. Amusing to read today, but this does

not mean he flew home. James borrowed one of his father’s wood planes. A plane is an

instrument for shaving off thin pieces of wood in long strips, to smooth lumber or to

reduce the thickness. There is a sharp chisel-like blade embedded on the bottom of the

wooden plane. It is pushed; blade down, over the wood’s surface, using both hands and

produces long, thin ringlets of shaved-off wood.

Plasterer – Mr. Booth. The interior walls of the houses were sometimes finished in plaster made from a lime mixture. This was the usual finish for ‘the second house’.

Potash Making Terms

The trees were chopped and piled to be burnt. When ready to burn, the piles were tended day and night until they had burnt out as it was essential not only to have fresh ashes but that the ashes not be rained on. These ashes were carefully collected, sifted, moistened and placed in leaching vats or tubs, the bottom being slanted, perforated and lined with straw and lime. Lime was not an essential item in the process, but produced a much better

product. The Coppings seemed always to use it. Boiling water was poured over the ashes and leached into letching pans placed under the vats. This residue was then evaporated over an open fire leaving the potash salts in the pan. Great care had to be taken to keep the ashes dry from the time they were burnt until they were finally packed into the barrel. The potash was put in barrels and taken on the two days journey by horse and wagon for delivery and sale in Montreal.

“Save his ashes.” This referred to the need to protect wood ashes whenever it rained. If the ashes were left out in the rain, all the lye would be leached out into the soil and lost. This term has come down to the modern business world in a slightly different form, but meaning about the same thing.

Letches – Refers to leaching vats where hot water was slowly poured through the wood ashes to ‘leach’ out the potash or lye solution.

Potato Growing & Harvesting – (See also: “Cutting, Potatoes” and “Drill, Potato” “Moulding” for descriptions.)

Hard frost, which kills the potato plant, is the signal that it is time to harvest the tubers and the potatoes are dug and stored underground. Farmers sometimes cut earth storage places in the side of a small hill to protect stored food from freezing through the winter or stored their root vegetables in a dirt or sand-floored cellar, if they had one.

Richard, Clemmer (Monsieur) – George spells this man’s name as Reshaw. A Canadian (Fr. Canadian) and maker of cedar shingles. The man’s given name is written variously as Clemour and Clemmer possibly it was Clement. There were several property owners with the surname Richard on the Township map drawn in the late 1840s.

Riddled – To pass material (meal) through a sieve or mesh to separate coarser material from a finer one.

Robinson’s – In Rawdon, it appears that Robinson’s was a drygoods store providing soap, candles, cloth etc. Everything that people couldn’t make for themselves and needed brought in from Montreal or imported from England. It was also a place to sell the excess production of some to those who didn’t or couldn’t make their own.

There were several Robinson families in Rawdon at this time but not all were related. This is probably a branch of the family from County Fermanagh which in later times owned a departmental store (or possibly a chain) in Ontario (and maybe elsewhere).

Rope – “Temporary” ones were made from bark and not bought pre-made. Likely they

used the inner, pinkish-brown cambium layer of tree bark, as this is very pliable and

could be twisted and braided into a rope which was not long lasting.

Salt – It isn’t mentioned where they obtained their supply of salt, but its very weight

would have made it an expensive commodity. At times, in the journals, George speaks of

people going to the store and other community members to get some. These trips were

not always successful. In the prairie areas of Canada it was easier to find deposits of salt

which had been formed by the drying up of sloughs or small ponds with no water inlet

our outlet.

Sawmill – Mr. Truesdelle’s, Monsieur LeMarle’s and Archambault’s are mentioned. There were many sawmills at Rawdon at this time. The name LeMarle does not appear in the listing of those receiving Letters Patent and so may have been a short term resident. (See Truesdell.)

Scythe – It has a very sharp, long, curved blade attached to a long handle meant to reap or

cut grain with a wide, side-to-side swinging motion with both arms extended and hands

on each of two handholds.

Sharp / Sharpe, Mr. – Sheep shearer. George Sharp (the family added an “e” in later

generations) and his family were from Kilglass, Sligo, Ireland and arrived at Rawdon

between 1832 and 1838.

Sheep Shearer – Mr. Sharp/Sharpe

Shoemaker – Mr. Hooey (John Hoey) made shoes and boots.

Sleigh – This is a winter conveyance for goods and people. When George speaks of a

sleigh being shod, he means having the blacksmith form metal runners to be attached to

the runners of the sleigh so it would glide more easily over the snow and ice. Without

this metal sheathing, the runners would wear out very quickly.

Sledge – a very low, sleigh type vehicle used to move heavy or bulky items such as

huge rocks or boulders. It was pulled by beasts of burden (horses or oxen). A sledge was

sometimes called a stone boat.

Soap making – Colonists would have made soft, brown, jelly-like soap, kept in a barrel and ladled out as needed. They would not want to waste valuable salt just to make hard soap, which could be cut in bars, stored and shipped more easily. Instead they would use the salt saved, for livestock health, table use and preserving meats and other foods.

Spinner

Wives and daughters spun yarn from the wool and flax that was produced on the farms and from this cloth was woven and garments were made. Those who could afford it also purchased cotton and higher quality wool, linen and silk cloth. George and Elizabeth Copping’s daughter, Mary, is mentioned as spinning at home and at her brother George’s.

Splitting out some Rails – Splitting (usually cedar) logs into rails to make fences for fields and pastures so that animals do not get into crops.

Splitting Shakes – Splitting off wooden shakes (shingles) for roofing or siding, which are usually made from cedar because cedar splits easily and is weather resistant. They were also very flammable and a spark from a chimney could spell disaster in a very short period. Snow on the roof helped prevent fires. A ladder was kept at the ready to allow access to the roof in case of fire. Many houses had a ladder permanently installed on the roof. George, junior, seemed to be the shingle maker in the family as there are references to his making shingles and family members getting shingles from him.

Sugaring Off Terms:

Sugar Kettle – Kettle used to boil off the excess water in the sap in order to make maple sugar. The sap was boiled until it reached the right temperature and then the kettle was quickly removed from the fire and the contents poured into moulds to harden. Most families used maple sugar almost exclusively. The sugar was shaved off with a knife or grater as needed to sweeten drinks, and baked goods. In areas where there were walnut trees and no sugar maples, walnut sap was collected and boiled to make sugar, or the birch tree could also be used. In the Rawdon area there were always sufficient maples to use for tapping. Later on syrup was made as well as sugar. To make syrup the sap was boiled to a lesser temperature. Taffy on the snow would also have been a treat enjoyed in a later period. Taffy is formed by boiling the syrup a little longer, but not long enough to make sugar. The thick, hot syrup is poured on the snow where it quickly hardens.

Hand carved wooden paddles were used to scoop up the sweet, sticky, treat. The Copping family made very little syrup, some vinegar with the last runs but mostly produced sugar.

Sugary – George Copping uses the phrases “at the sugary” and “in the sugary” to refer to both the sugar bush or woods where the trees were and the cabin (from the French cabane) or shanty (from the French chantier) where the syrup and sugar were refined.

The Copping farm had a large percentage of sugar maples on it. When they actually built a sugar cabin, or shack as it is called in some areas, it was within a few feet of the house, right by the roadside. Neighbours going to and from the village stopped by for a visit and a drink of hot sap.

In some areas the sugar bush was quite a distance from the house and the family members involved in sugar production would move to the sugar cabin for the duration of the run. In Rawdon, because the sugar bushes were relatively close to home, this was not done.

Tanner or tannery owner – He bought raw hides from the settlers and sold them leather to make shoes, moccasins, crude machine belts, and harness-making etc. He would use potash or lye in his tanning process.

Threshing – The grain stems with the ‘ears’ of seeds intact, were trampled and beaten to release the individual seeds from the ears or seed heads. Next the husks or shells (now called chaff) and seeds were winnowed in order to separate one from the other. A large, flat basket would be filled with the threshed grain on a breezy day. The person would toss the contents of the basket lightly into the air, where the breeze would blow the very light chaff away and the grain would fall back into the basket. George called this winnowing process “cleaning grain”. The grain was now ready to be fed to animals as is, or taken to the miller to be crushed into meal or flour. The chaff was used to feed or amuse the poultry and the straw for bedding animals in the stable. During hard winters if there was not sufficient hay to last the winter, straw could be fed to the animals to supplement the meager or dwindling supply of hay, otherwise it was used for bedding for the animals, and to stuff mattresses, particularly for the children’s beds.

Tough – Strong cord or thread, possibly made from linen fibers

Train – To train or draw along. In this case to pull a heavy load, sometimes joined

together with chains like cars pulled by a locomotive or train. In the Diary a train refers to

what was later called a bobsled. This was a sleigh with two sets of runners or “bunks”.

These bunks were held together with a long pole and chains which allowed the length of

the sleigh to be adjusted depending on whether it was used to haul firewood or logs.

Whether or not it was fitted with a box also depended on what it was used for. Logs or

lumber did not require a box. This type of sled was very useful in the bush as its body

was flexible and it was easier to get around what were sometimes steep and sharp curves,

as well as trees that were fallen, or even those still standing.

Troughs – Wooden troughs or channels to direct the flow of the sap. Troughs were also used in the making of potash.

Truesdell, Mr. – Daniel Truesdell was of Loyalist origin although possibly born in Quebec. He married a Dugas daughter. The surname has many variations but his descendants are mostly known as Trudel.

George Copping purchased a ¼ pound of tobacco from him on May 18, 1840. Truesdell may have kept a small shop at the mill or possibly grown the tobacco himself.

Up the township – this refers to the higher ranges, George’s farm was on the sixth range and so higher ranges would be “up the Township”. George actually referred to going ‘up the township to Johnston’s” and Sharp’s who were on the 10th Range.

Water Furrows – channels dug to divert and drain waters which otherwise would flood a field, road or building. Low-lying fields were also ‘ditched’ for drainage. These ditches or furrows were dug by hand.

The Journal

DIARY OF GEORGE COPPING

Friday, January 1st, 1836

to

Thursday, July 3rd, 1845

Born

11th June, 1780 in Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex Co., England

Married

ELIZABETH SAGGERS, in London, 5th June, 1806

Sailed for Canada on the SS “Lively”, 5th May, 1811

Landed in Quebec 2nd July, 1811

Friday, 1st January, 1836. This is a fine ….(original partially destroyed)…we were down at George’s place……..

day the boys were up at Mrs. Bo…….

Saturday, 2nd January, 1836. This is a fine day and the boys James, Thomas and Henry were at work for Ed. McGee. I was threashing some oats and cleaned up 6 bushells and my wife was over to Mr. Oneals paying him for…… £2.5.0 A most beautiful night.

Sunday, 3rd January, 1836. This is a fine day and I am very sick with a cold. 5 of the children were at church. Mr. Law was here and dined with us.

Monday, 4th January, 1836. This is a dull day rather ……….. James is gone down to Mr.Dugas to work and Thomas & Henry are over at Mr. Petrie’s with the oxen drawing wood &c. work we are due to them. I have been threashing some oats. Joseph is over at the Norish’s for part of a day. Mary & Eliza are at school. James came up again …… was here and got ½ bushell of Salt ½ lb. coffee 2/6.

Tuesday, 5th January, 1836. This is a fine day and we have James B…. and his oxen helping to draw firewood. Mary, Joseph and Eliza are at school. George was up today and took his fan down.

Wednesday, 6th January, 1836. Blows fresh from the northward. Had a fall of snow. James and Thomas are at work at James B….. Henry aboout home. My wife at Mr. Lowler’s as his wife is sick. I have been threashing some oats. Mr. Boice called and gave me a Direction to Ireland and I was over at Mr. Law’s taken up note between us for Hay.

Thursday, 7th January, 1836. This is a fine day and the boys are gone to the Meadow drawing Hay. My wife came home early this morning from Mr. Dowler’s and our Mary is gone over to help them a while. I have threashed a few oats &c. 5 loads myself 5 loads Wm. 5 loads George.

Friday, 8th January, 1836. This is a fine day and Thomas and Henry are over at Mr. Dowler’s cutting wood for him. James and I fetched out the last of the hay out of the meadow. I have threashed out some oats. John Booth borrowed my long saw to-night.

—————————

Wednesday, 20th January, 1836. This is a fine day and the boys have drawn some firewood and I have been threashing some wheat &c. Petrie is away to QUEBEC I believe, George was up to-night.

Thursday, 21st January, 1836. This ia s fine day but cold and I have been threashing a while at some wheat and …. it comes on to snow. Thomas and the …. fetching hay for Wm.

Friday, 22nd January, 1836. This is a blowing ….. day and I have been cleaning oats for Mr.Petrie and the boys have been fetching oats down to Wm’s. and 2 loads of straw for ourselves.

Saturday, 23rd January, 1836. This is a blowing drifting day and Thomas has fetched some chaff from Petrie’s and then cut some firewood. Henry at work for Mr. Dwoler. I have been threashing some wheat &c. Petrie was here on his way down to Mr. Holmes. James came home to-night.

Sunday, 24th January, 1836. This is a dull day and James and Mary are over at the Village at Church if Mr. Reid is come home. Joseph and Eliza are gone over to Mr. Dowler’s.

Monday, 25th January, 1836. I have been over to Petrie’s and have threashed a few oats and the boys fetched some chaff and straw and cut some firewood.

Tuesday, 26th January, 1836. This ia a cold day and I have been threashing some wheat &c. Boys are cutting a little firewood &c.

Wednesday, 27th January, 1836. This is a cold day with a little snow and I have been busy cleaning up 9 bushells of wheat and the boys Thos. and Henry are gone down to Mr. Dugas’ Mill with 10½ to make flour for Town. Molly Dunn came here today. Wind from the Northward. Henry came up with some oats.

Thursday, 28th January, 1836. This is a cold day and I have ben cleaning up a few peas for Mr. Petrie and Henry is cutting some firewood for them. I began to threash some oats and Thos. came up from the Mill this morning.

Friday, 29th January, 1836. This is a cold day with a little snow and I have been over to Mr.Reid’s and Thomas is at school as his finger is sore. Henry is at Mr. Dowler’s cutting and drawing wood and I have cleaned up 3 3/4 of oats.

Saturday, 30th January, 1836. This is a fine mild day with a little snow and Henry and Joseph are down at the mill at Mr. Dugas’ for some flour and seed. Thomas has been helping Wm. draw some wood and then he went over to Mr. Norish’s to get his gun lock fixed. Henry & Joseph came up about the middle of the day. Molly Dunn came here tonight. George was here a while and James came up this evening. Wm. Marlin was here a while.

Sunday, 31st January, 1836. This is a mild day with a little snow and James and Thos. are gone to church at Kildare and Molly Dunn is starting for Home and Mary is gone …. young Robert Pollock was over here for Henry ….

Monday, 1st February, 1836. ….. day and I have been threashing a while. James is gone down to Mr. Dugas. Thomas is in the house with a sore finger. Henry has been getting some wood for shafts &c.

Tuesday, 2nd February, 1836. This is a very cold day. We can do but little, we are obliged to keep the cattle in today. Mr. Reid the minister called in.

Wednesday, 3rd February, 1836. This is a very cold day and my back is so bad I am scarcely able to do anything. The boys have got a little wood and they are able to do but little. Mrs.Petrie was here a while. Thos. was down at Mr. Robinson’s for some tea.

Thursday, 4th February, 1836. This is a cold day and my back is something better. Thomas and Henry are about the house most of this day. I was helving a fork or two that wanted helving this some time.

Friday, 5th February, 1836. This is a cold day and the boys are cutting a little wood &c. I am better with my back but not able to do much. I have attended the cattle &c. and made a wooden rake. Mrs. Petrie was here and Wm. Brown.

Saturday, 6th February, 1836. This is a fine day not quite so cold as yesterday was and the boys are getting some wood and they are getting some oak bark for Mr. Dowler’s sore leg as he is not able to get it himself. I have cleaned up 6½ bushells of oats.

Sunday, 7th February, 1836. This is a fine day and my wife and myself, Thomas and Eliza were at church and called in at Mr. Truesdell’s and went down to George’s place. James came up this morning and George brought us up in his sleigh tonight.

Monday, 8th February, 1836. This is a very heavy fall of snow. Henry is at Mr. Law’s today as he is sick. Wm. and Thos. made a travoy for the train. I am terribly bad with the toothache this 4 nights.

Tuesday, 9th February, 1836. This is a stormy day and the boys can do but little as the snow is very deep and Thos. and Joseph went down to school. I blistered the back part of my neck for the toothache.

Wednesday, 10th February, 1836. Blows very hard at times from the Southwest. Thos. and Henry are getting some firewood down, the roads are very badly drifted up. I am in the house today as I am able to do nothing out.

Thursday, 11th February, 1836. This is a fine day and I have got rid of the toothache and I have done but little today. The boys are getting down a little firewood. Petrie and his wife were here this evening.

Friday, 12th February, 1836. A little fall of snow and my wife is down at George’s as his son George is sick and Thomas is …. Henry is gone down to the Mill to take a load ……. Petrie was here a while tonight and my wife came up …… late in the night.

Saturday, 13th February, 1836. This is a fall of snow which gets deep now and young Petrie was here and Thomas and he are gone down to George’s place and I am better but I am very sore as yet, I can do but little. Henry came up from the Mill this evening.

Sunday, 14th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and my wife and Henry are gone down to George’s place and John Pollock is here and Dowler was here a while.

Monday, 15th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and I have been threashing oats a while. The boys are getting a little wood and Jospeh is down at George’s taking Mary down and David Petrie came with James from St. Rocks.

Tuesday, 16th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and I have been down to Geroge’s, Mr. Reid’s and up to Brown’s and I have been up to Mr. Reid’s this evening. I cleaned up 2½ bushells of black oats this morning.

Wednesday, 17th February, 1836. This is a fine day but very cold and Wm. and Thos. started for MONTREAL about 4 o’clock this morning and I have begun to threash a little wheat. Henry drew down a little dry wood for the Fire &c.

Thursday, 18th February, 1836. This is a fine day but very cold and I have cleaned up 1½ bushells of wheat and sent Henry down to Mr. Dugas with it to be ground and my wife is gone to George’s and Truesdell’s &c. Mr. McGee was here.

Friday, 19th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and Henry came up from the Mill with the flour and some stuff for the cattle. My wife and Joseph are down at Mr. Robinson’s getting shirting and different things. I have the toothache. Henry fetched up a load or two of dry wood &c. Mrs. Petrie was here.

Saturday, 20th February, 1836. This is a fine mild day to what it has been this week past and Henry is drawing some firewood. I am but poorly; I can do but little, attend the cattle &c. Henry has been up to Petrie’s for sundries. This evening snowed a little.

Sunday, 21st February, 1836. ………. my wife was down at George’s place and then she went …….. John Pollock was here most of the day and David Petrie was here …….. thawed today some. Mary is still at George’s since Monday last. Wm. and Thom. came home tonight.

Monday, 22nd February, 1836. This is a fine day and thaws and the boys are getting a little dry wood down, they are doing but little today as Thomas is tired coming from MONTREAL. Henry was down at Mr. Dugas with some things for James and came up about 11 o’clock tonight and we find by him that Patty Dugas child is dead.

Tuesday, 23rd February, 1836. This is a mild day with snow and my wife has been down to George’s to see the child and Thomas and Henry are chopping for Mr. Dowler. I have been threashing wheat a little. Comes onto rain tonight.

Wednesday, 24th February, 1836. This is a mild day with rain and Thomas and Henry are about all day today and I have cleaned up ½ bushell of seed wheat &c. and it comes on a very heavy snow storm with the wind from the Northward and it blew our barn down. Mr. Gray was here tonight, all of us middling.

Thursday, 25th February, , 1836. This is a terribly stormy day and we had Mr. Gray and Wm bargaining for a horse and cow and different things and we spend the day in a very rough way but we must put it all by. Henry was down at George’s place. John Pollock was here tonight. I have done wong this time, rather too much so.

Friday, 26th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and I am but very poorly. The boys began to clear some of the barn away and I have been picking a little wheat out of the snow but I am poorly with boils.

Saturday, 27th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and Thomas is at Mr. Edward McGee’s at work for David Petrie. I have cleaned up 3/4 of a bushell of seed wheat and ½ bushell of grass seed. Henry is cutting a little firewood then went down to George’s for the horse &c.

Sunday, 28th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and I am very bad with a boil still and James came up this forenoon and Mr. Dowler and Mr. Marlin were here and George came up as his child is very poorly as yet.

Monday, 29th February, 1836. This is a fine day but cold till the evening then it comes on to snow and the boys are cutting a little firewood about the house &c and at ……. James went down to Mr. Dugas this morning.

Tuesday, 1st March, 1836 This is a milder morning with a fall of snow and my wife and Joseph are gone up to James Brown’s to get a jacket and trousers cut out for Joseph. Thomas and Henry are about the house cutting firewood &c. Little Thomas Boice came here today and Wm. Thos. and Henry measured off 1 acre of wood.

Wednesday, 2nd March, 1836. This is a cold day and drifts so that the boys are doing but little out and I am so bad with my back it is so sore I am able to do nothing at all. Little Boice is here today.

Thursday, 3rd March, 1836. This is a cold blowing drifting day and Thos. & Henry are cutting a little firewood and my wife is gone over to Mr. Edward McGee’s respecting my deed Money. Thos. Boice is here today.

Friday, 4th March, 1836. This is a mild day to what it has been for some time past and the boys are getting a little wood down. George was up for Mary and she is gone down to his place and the others are at school. Little Boice is here at school with the Children. The cattle have pulled some of the wheat out of the side of the barn &c. Mr. Petrie was here tonight.

Saturday, 5th March, 1836. This is a rather blowing and drifty day and Henry has been over to Mr. Norish’s to take a couple of ploughs to be repaired and an axe to be laid &c. Thomas is chopping a while and then he is cleaning out the Cows &c. My back is something better but very sore as yet. Freezes very sharp tonight.

Sunday, 6th March, 1836. This is a very stormy cold day and my wife, Henry, Joseph and Eliza are at Church and John and James came up shortly after as he is 25 years old today. My back is getting better thank God.

Monday, 7th March, 1836. This is a fine day and Thomas and Henry have been threashing a little wheat and I have cleaned up 1½ bushells and the boys have been fixing their axes for chopping.

Tuesday, 8th March, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and the Boys are chopping for Mr. Dowler and Thos. & Joseph went down to Mr. Dugas with 1½ bushells of Wheat.George’s child is very sick. I have been to Mr. McGee’s and to the school house &c., then I threashed out a little wheat for seed &c.

Wednesday, 9th March, 1836. ……….. is a fine day and the boys are chopping for ……. Pollock is with them today. Thomas came up from the Mill. Lost his horse and came up without him. Joseph found him and came up with him. My wife is down at George’s as his child is very sick and Wm’s. wife and one of the children are sick. Thos. was over at Mr. Law’s and Henry was at Mr. Lindseys for castor oil for Peggy but could get none.

Thursday, 10th March, 1836. This is a fine mild day with a fall of small snow and Thomas is at Mr. McGee’s chopping and Henry is gone for a load of Ashes for Wm. Children are at school. My wife was down at George’s seeing the child, it is very sick yesterday and Joseph is with her I Bo’d &c. This should have been in yesterday. Mrs. Gray brought two Turkeys down today. Comes on to rain heavy tonight.

Friday, 11th March, 1836. This is a terribly windy day and freezes sharp and Henry is gone down to the mill for the flour that was left and took a Bushell of wheat for Vetrie’s and brought the flour up. I was threashing a while. Thos. is in the house. Young Petrie was here. I cleaned up 1½ Bushells of the seed wheat.

Saturday, 12th March, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and the Boys are chopping for Mr. Dowler and John Pollock is with them. I have been threashing a little wheat. Henry is gone over to Mr. Norish’s with an axe to be laid. David Petrie came for his flour this evening &c.

Sunday, 13th March, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and James came up this morning and we hear that George’s child is very poorly indeed. George was up here. My wife has a swollen face from the Cold. James and Susan Brown were here getting Ink and paper. Comes on to snow to night.

Monday, 14th March, 1836. There is a fall of snow and James is gone down to Mr. Dugas to work and Henry is cutting firewood a while. Geroge brought me a Bushell of Peas at 3/6 yesterday. My wife’s face is swollen still. Her eye is nearly closed.

Tuesday, 15th March, 1836. This is a cold day but fine and the Boys are chopping for Mr. Dowler. I have threashed a little wheat. My wife has her face swollen and Wm’s. little Boy Wm. is very sick and George’s little George is very sick as yet. I sent a letter to Charles.

Wednesday, 16th March, 1836. This is a fine day and the Boys are chopping at Home today and Wm. ……….. to fetch a load of ashes. I am threashing a ……….. My wife is poorly with her face and Wm’s child is very ill and Thos. is gone down to George’s this evening. Sharp night.

Thursday, 17th March, 1836. This is a very stormy day with snow and sleet and rain &c. Boys were chopping a little while at home. My wife has been up to Mrs. Brown’s to get a little BLOOD took from her and she finds herself something better tonight and the two children are very bad. I put by 2 Bushells of seed wheat.

Friday, 18th March, 1836. This is a stormy day at times it blows hard and snowstorms. Henry is gone for ashes for Wm. Thomas chopping at Mr. Dowler’s and Joseph have the Ox down for a load of Potatotes for Mr. Dowler. George and Wm’s. children are very sick and my wife is rather better, thank God for it and hear that Clara has gone off somewhere but we do not know where.

Saturday, 19th March, 1836. This is a fine day but cold and the Boys are chopping for Mr. Dowler and finished one Acre for him and my wife and Joseph are down at George’s place and the child is very bad and Wm’s. are both sick today. I have been threashing a little wheat.

Sunday, 20th March, 1836. This is a fine day and I and some of the children were at Church and behold I saw my Daughter which surprised me that she should have a face to be in Church where she is known and knows the state she lives in. I have been down to George’s and the child is very ill and James is come up this afternoon.

Monday, 21st March, 1836. This is a sharp morning but is a fine day and the boys are chopping at home today and I have threshed some wheat a little while. William’s children are very ill indeed. My wife and James were down at George’s and the chld is very sick. Old Mr. Rogers was here tonight and about three or four more besides our own family.

Tuesday, 22nd March, 1836. This is a fine day and James is at work at Mr. Petrie’s today and Thomas and Henry are at home. My wife sat up with Wm’s child last night and it is very bad and George was up for our Ox as his horse is very sick and his child and Joseph is gone down with him to draw wood &c. WILLIAM’s child died tonight at 25 minutes after 8 o’clock and we were there till about 2 o’clock. We has our old horse to …… Mrs. John Robertson.

Wednesday, 23rd March, 1836. ………. and my wife is gone down to George’s place and …… and the child George died about 12 o’clock. I have been threshing awhile and Joseph came up from George’s place with the Ox and George was here looking for some boards to make a coffin. This is a sharp night.

Thursday, 24th March, 1836. This is a fine day and my wife came up from George’s this morning early and James is gone down to the mill with 5 bushells of wheat and Thomas and Henry are cutting some wood for the fire and I am threshing awhile. Eliza was down to George’s this forenoon and Henry Law is here making the two coffins. Rebecca Petrie is at work here a while today.

Friday, 25th March, 1836. This is a fine day but the wind is cold and we are starting to the 4th Range to George’s place to bury the two little babies and did meet with a pretty good Assembly and about 12 o’clock we proceeded on in good order and everything quiet and we returned to George’s place a while then came home and our Boys are gone to the wake of Mr. Carr’s as his Daughter is dead.

Saturday, 26th March, 1836. This is a fine day and four of the Boys are gone to

Mr. Carr’s Daughter’s burying and I have been threshing awhile and my wife is very poorly.

Sunday, 27th March, 1836. This is a mild morning and James is gone over to Ramsey and Henry is over to Mr. Pollock’s. George and his wife and Wm. and his wife and sister and young Boice came and stopped here. My wife is very poorly &c.

Monday, 28th March 1836. This is a fine day and Henry is at work at Mr. Pollcok at Wm. Marlin’s and Joseph is fetching Ashes for Wm. with the Ox and the Horse and James came home from Ramsey about the middle of the day. I have threshed some wheat and Mrs. Petrie was here on her way to Mr. Robinson’s. Mr. Edward McGee was here a while.

Tuesday, 29th March, 1836. This is a fine day and Thomas and Henry are at work for Mr. Pollock. James is at home and Joseph is fetching a load of ashes for Wm. with the Horse.

Wednesday, 30th March, 1836. This is a fine day and my wife is over at Mr. Law’s as his wife is sick and put to Bed with a Boy about 12 o’clock and James has bought a Load of Lime at what we may call 8/- and the Boys are ……. fetched 10 bushells of potatoes from Mr. Pollock’s ….. for a sleigh and chopping. I have been over to Mr. McGee’s this morning and evening, about some Rails splitting &c. Davide Petrie has our sleigh to go to St. Jacque’s.

Thursday, 31st March, 1836. This is a fine day and the Boys are at the Sugary and D. Petrie helping them. I have threshed a little grass seed and put up ½ bushell of wheat.

Friday, 1st April, 1836. This is a fine day and the Boys are at the Sugary and I have been threshing some Black Oats and cleaned up 4½ bushells and Joseph and the Horse are gone down to St. Paul’s for a load of Lime for Wm. Thaws fast this day.

Saturday, 2nd April, 1836. This is a fine day and Joseph and the Horse are here, came up about 9 o’clock this morning and the Boys are at the Sugary and I have been threshing Black Oats and cleaned up 3½ bushells. James was up to Le Marles to speak for 2 buckets and 1 washtub.

Sunday, 3rd April, 1836. This is a fine morning and Henry is down at George’s for a sap barrel and myself, James, Mary and Eliza were over at the Church. The rest of the Family were at Home and the roads are very soft as it thaws fast today. Mrs. Nancy has been in our house today, she has not been in for this 3 YEARS before I believe as she has been unbearable an a bad neighbour but she must comply or keep her own side.

Monday, 4th April, 1836. This is a cold morning but a fine day with a strong breeze from the Northeast and the Boys, James, Thomas and David Petrie are over at Mr. McGie’s. Henry is at the Sugary and Joseph and I have threashed some Black Oats and cleaned up 4½ bushells and our cow Jersey calved this afternoon a Heifer Calf.

Tuesday, 5th April, 1836. This is a sharp cold morning and the wind from the Northward. James, Thomas and David Petrie are at Mr. McGie’s splitting rails again today and I have been sugaring off 9½ of sugar. Henry was after a bucket for the sap.

Wednesday, 6th April, 1836. This is a cold day and the sap don’t run today and Henry and Joseph are in the sugary a while and I have been threashing the last of the Oats and cleaned up 3 bushells and I am very poorly with a cold and we hear of Mr. Rob’s dieing today.

Thursday, 7th April, 1836. Henry and Mary and Joseph are gone over one way and the other. Henry is at Mr. Norish’s, Mary and Joseph up to Mr. Ty …… of 2½ bushell of seed wheat &c. Our Nanny calved this afternoon a Heifer Calf Nan and James and David Petrie came home from Mr. McGie’s. Old Mr. Rogers was here and I gave him a Peck of seed wheat. I am very poorly with a cold.

Friday, 8th April, 1836. This is a fine day and my wife and myself and James were over to Mr. Hob’s to follow him to be buried and a great many people were there and we stopped a while at Mr. Truesdels and Thomas is at work at Mr. McGie’s and I am something better today and my wife is poorly with her hands and arms. Comes on to rain tonight. Thomas came home tonight. Henry and Joseph at the Sugary.

Saturday, 9th April, 1836. This is a rainy and cold day with the wind from the Northward. James is down at Mr. Dugas Mill with 3 bushells of wheat and my wife sugared off 8 lbs of sugar.

Sunday, 10th April, 1836. This is a terrible stormy day and it storms from the Northward with high wind and snow. Petrie was in a while.

Monday, 11th April, 1836. This is a fine day and James and Thomas are at work at Vetrie’s and Henry and Joseph are in the sugary emptying the Troughs & made a few and Petrie and his wife were in a while and my wife has made a little sugar and a little syrup and I have been about the barn throwing out the dung &c. and cut a few potatoes. Sugared off 11½ and Joseph has cut his back with the round axe and I have been down to Mr. Robinson’s and got some Tea and cord for Reins &c.

Tuesday, 12th April, 1836. I have been down to Mr. Robinson’s with 2½ bushells of Oats and brought up 6 Bushells of Potatoes from George’s and he had a cow died this morning and James and Thomas and David Petrie are chopping for us. It is a cold day. My wife’s hands are very bad indeed.