Quebec City

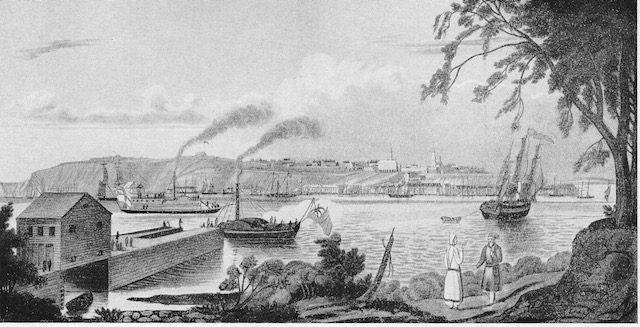

As the S S Lively sailed into the Quebec harbour this would have been their view of Quebec.

Notice the steamships, which had been on the St.Lawrence River as of 1809.

The S.S. Lively had sailed some 350 miles from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River into the Quebec harbour.

In 1811 Quebec City, although it could not boast to be old in comparison to European cities, was far from being a new settlement. Founded in 1608, it was second in age only to Louisburg in Nova Scotia. (In 1605 Champlain had left a few men to winter in Louisburg.)

Quebec was also the busiest port in North America. During the high season there could be upward of 300 vessels, from canoes and barges to European passenger and cargo ships in port waiting to be unloaded.

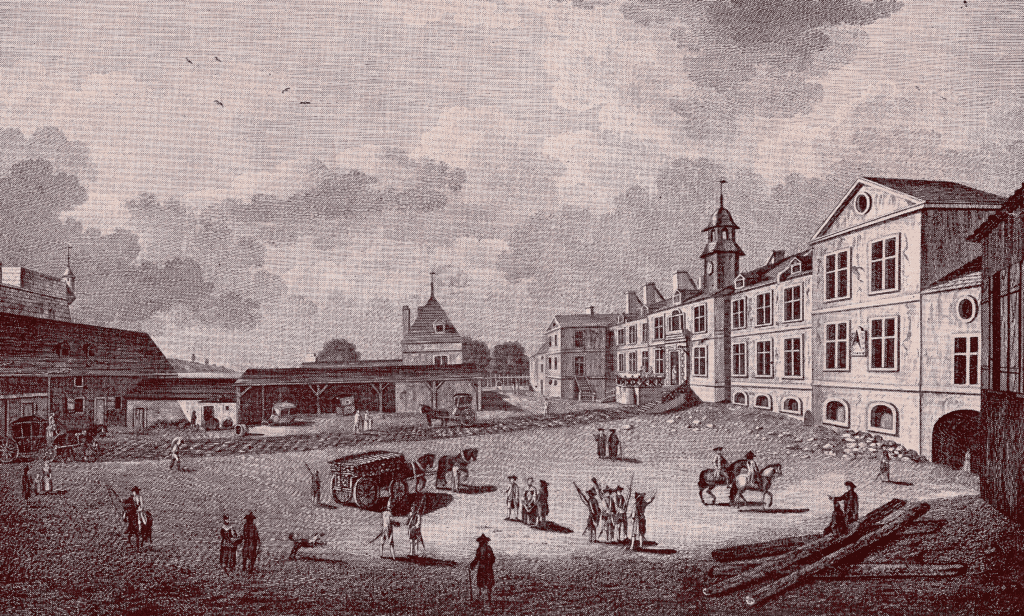

Quebec, is proudly seated on Cape Diamond, on the Northern banks of the St. Lawrence River. The lower town at the foot of the promontory was crowded with buildings of shipping merchants. Warehouses and stores were built on the wharfs. The streets were narrow and not very clean.The ascent to the Upper Town was narrow and irregular. The appearance of the buildings improved as you advanced upwards. Buildings mostly of grey stone with high sloping roofs generally covered with tin or sheet iron.

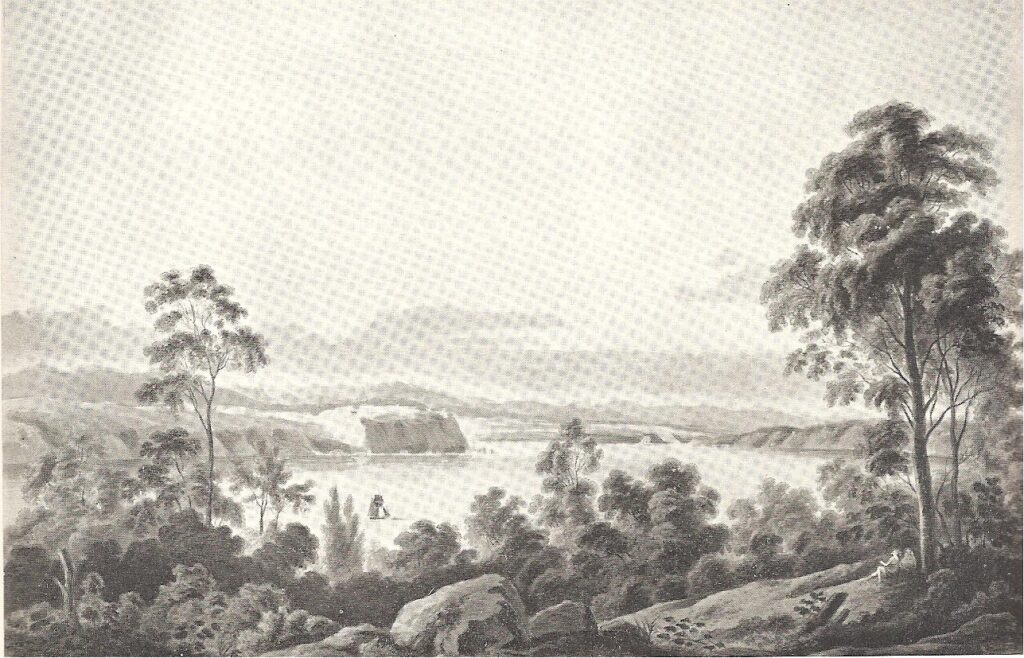

The view from the ramparts of The Citadel of the celebrated Plains of Abraham were scarcely to be equalled.

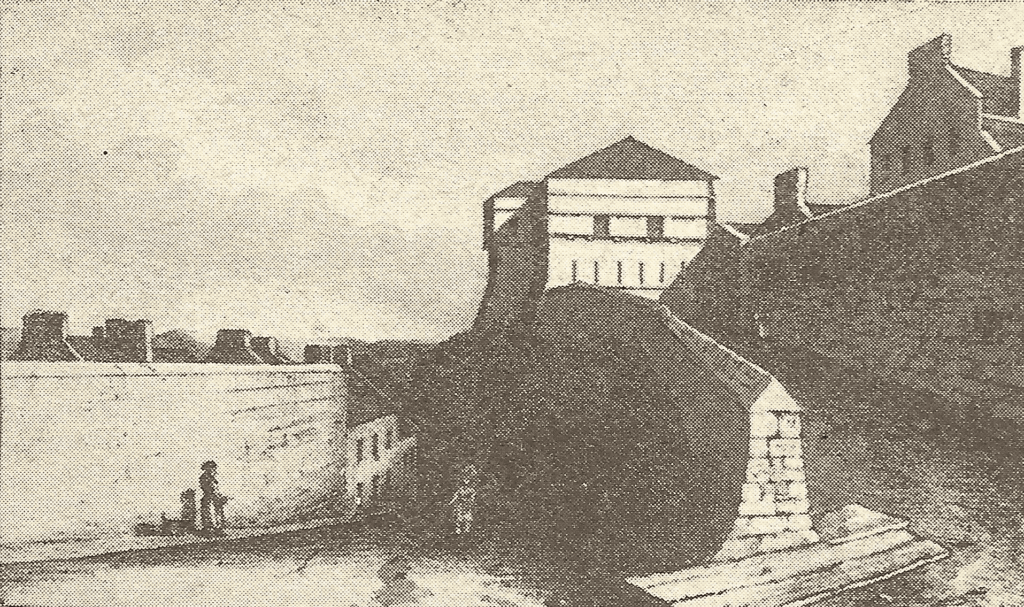

The citadel was built on the edge of the rock 350 feet above the St. Lawrence River. The governors residence and other public buildings as well as the monument to the memory of Wolf are all in this Upper Town.

When the Coppings arrived in 1811, Quebec had been under British rule for only or already, (depending how you see it), 44 years. Architecturally little had changed from the previous French regime. The major reconstruction required as a result of Wolfe’s persistent and heavy bombardment was mostly done to reflect the original style although the functions had changed to reflect the new administration. The repairs had begun immediately upon the arrival of the English military and by 1811 was mostly completed when the Copping family debarked in their new home.

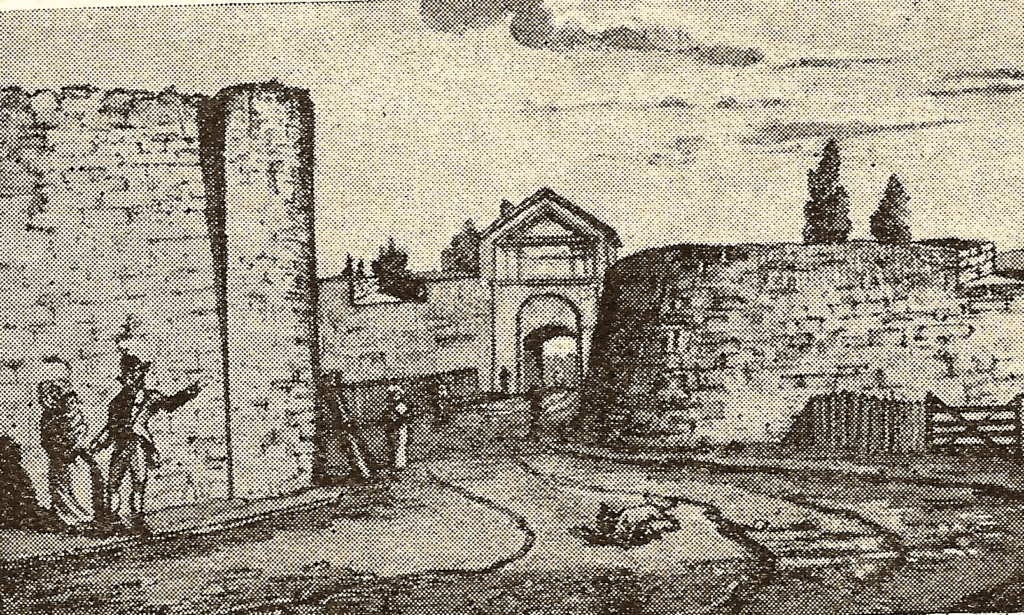

Quebec City was also the only walled city in north America. Originally with three gates leading into the city, the St. Louis Gate, the Palace Gate and the St. Jean Gate. The British expanded the number to five gates. During their four year stay in the area of Quebec City, the Copping family would have become familiar with the historic town.

Between the St. Louis and St. John’s gate was a fine esplanade, the usual place of parade for the troops of the Garrison.

The Upper Town is entered through a fortified gate from which streets verge in various directions. One of these streets leads to a large spacious square. The streets in this part of the town are wide, and the houses large and respectable. The population is about 30,000 or more.

The government has spent large sums of money upon the fortifications of Quebec which are almost impregnable. The walls of the Citadel are 40 feet high in the ditch about 50 feet wide cut. The Plains of Abraham extend to the west and the main road to Montreal.

The inhabitants of Quebec are of various nations French Canadian, English, Irish, Scotish, Americans, Indians, and various others. Law proceedings were conducted in English and French being the common languages used here.

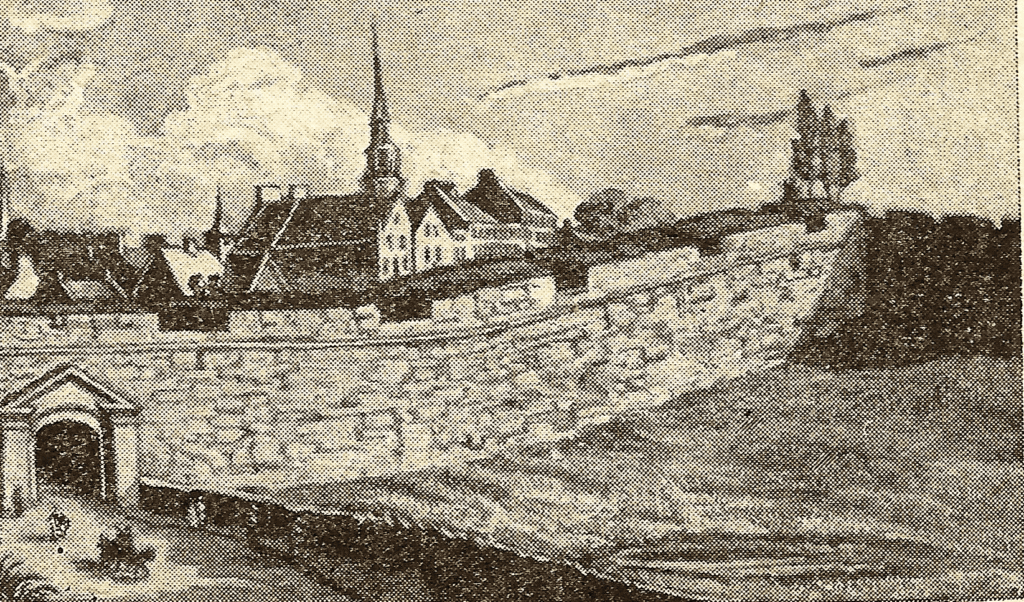

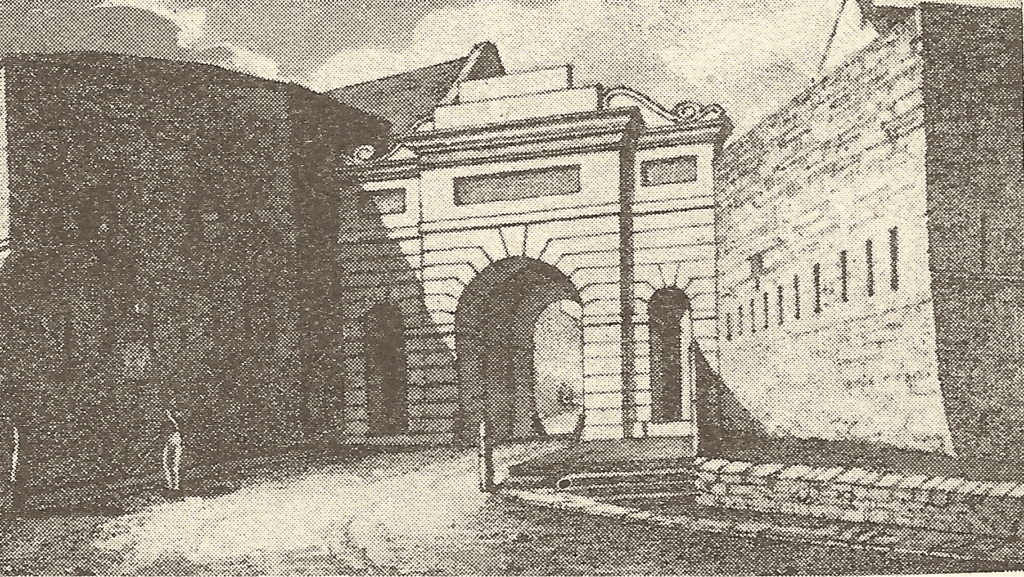

Bishop’s Palace after Reconstruction.

In 1811 the reconstruction of the Bishop’s Palace, one of the many buildings destroyed by the British bombardment had been completed. It now held public offices and a library. The chapel was converted into a room for the meeting of the Provincial Assembly of Representatives.

Notice the Palace Gate which allowed entry from the Lower Town, which was rebuilt, as well.

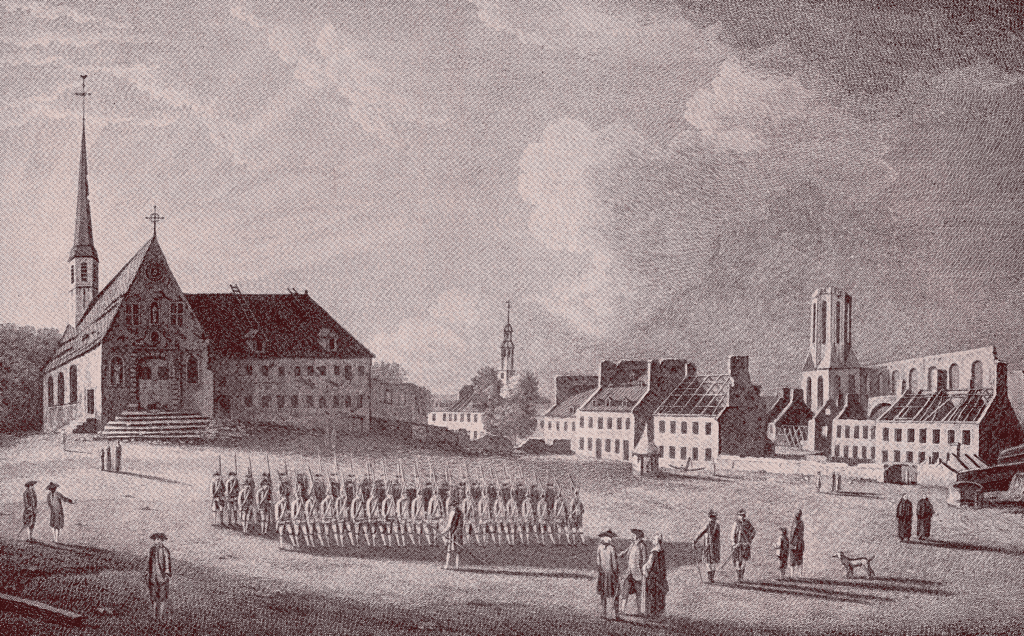

Catholic Cathedral

1759 R Short

A very imposing building, the Catholic Cathedral was a large stone structure with a steeple that rose high above its roof. It could seat 3,000 people. The final touch, a new organ, had been installed about 5 years before the Coppings arrived in Quebec City.

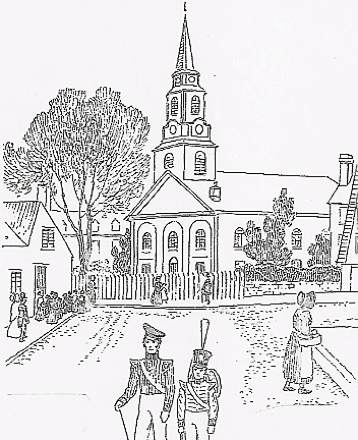

Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City

This is the earliest known drawing of the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Quebec City. Consecrated August 28, 1804, it was the first Anglican Cathedral built outside the British Isles.

It was designed was after Saint Martin in the Fields in London.

Although the outside gives the impression of austerity, the inside lacked any hint of such severity. The benches were made of oak, ironically imported from the Royal Windsor Forest . An especially designed sovereign’s seat is located in the Royal Box in the balcony.

As well as funding the construction of the cathedral, King George III donated a Bible and the silverware required for use during services. He also provided the prayer books to be used by the congregation during services.

Nestled in the heart of Old Quebec, it was the mother church of the Diocese of Quebec and had two parishes, Quebec Parish and the Parish of All Saints which included Canada East and West

Its set of eight change-ringing bells was built in London by the same foundry that cast Big Ben. These are the oldest such bells in Canada. The bells way from the largest at 1850 pounds to the smallest at 646 pounds.

Over the years the City of Quebec has asked the church to ring it bells on special days such as Christmas, New Years Day as well as special celebrations such as a celebration for the founding of Quebec City.

These two bell towers have also been visited on a number of occasions by special delegations of bell ringers from the United States, England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Australia.

George and Elizabeth’s two children born in Quebec City, Clarinda and James, were baptized in this church.

In 2006 a major project, a full restoration of the bells. They were sent to their original foundry in White Chapel, England.

The cathedral can be visited today.

Quebec City was the major port in the Canadas. Lower Town, at the base of the promontory, wrested from the cliffs on one side by mining, and expanded on the water side by the construction of wharves that reached out over the river. The river at this point was approximately a mile wide and 35 fathoms deep. The tide rose about 3 fathoms, but in the spring it could go as high as four.

The Lower Town was the centre of commerce and industry. Ship building had started some 20 years earlier and was now a major industry. Ships of all sizes and descriptions were built here. Wood for the construction was abundant locally. Anchors, cordage, and sails were imported from Europe.

Large store houses were built in the port area by wealthy merchants who imported goods from the old country for distribution in the Canadas. Although the colony was becoming self-sufficient, there were still many articles that had to be imported, especially in textiles, lace, fine china, and other luxury items.

In 1811 Quebec City offered good promise of employment for new arrivals. The British military was preoccupied with reinforcing existing fortifications and building additional lines of defence in view of a growing threat of invasion from the newly formed United States. Men were needed for all kinds of work, from craftsmen to labourers, the last being the most urgently required.

Masons and stone-cutters, builders, lime burners, carpenters, sawyers and axemen, teamsters, blacksmiths, pulley makers and edge-tool makers, wheelwrights and harness makers, diggers and packers could all find employment with the military or, preferably private contractors who paid better wages.

Working conditions, although unacceptable today, were comparable to those in the British Isles and France. A typical summer’s day would begin at five in the morning. At 8 o’clock there was a half hour break for breakfast after which they return to work until noon. After lunch they returned to work until seven in the evening. If the job was urgent, after a half hour break for supper they worked until dark.

Winter months required a rescheduling of work hours. They would start at eight in the morning and have only an hour for lunch, after which they worked until sunset.

On very rainy, stormy summer days, or very cold, blustery, winter days when it was impossible to work the wages were docked.

Neil Broadhurst, a longtime researcher the Coppings gives the family’s location at Quebec as in the Parish of St. Jean on the Ile of Orleans.

Documents show George found employment in the Patterson Sawmills in nearby Montmorency.

One mill in the QuebecCity Area had 360 saws.

Mr. P Patterson, became the proprietor of the extensive sawmills at Montmorency now owned by the estate of the late George Benson Hall, his son-in-law.

Peter Patterson, about 1719, left Whitby, England, to seek his fortune in Canada. His skill of the shipbuilder, his integrity of character and business habits, later on as a partner in the wealthy Baltic firm of London merchants who had representatives in the colony. At the time of Napoleon’s Continental blockade, the English government, seeing that the Baltic was closed for the supply of timber for the Navy, gave out a large contract to Mr.’s Henry and John Osborne for masts and oak. This company employed Mr. Patterson to dress and ship this timber. A timber license, of portentous import, authorizing the cutting of oak and masts for the Navy in all British North America was issued. Under authority of this license Mr. Patterson partly denuded the shores of Lake Champlain as well as the Thousand Islands of their fine oak. Mr. Patterson was the first to float oak logs into Quebec. He built a large mill at Montmorency that soon attained great importance in the area.

Adapting to a New Country

The exact day the S.S. Lively arrived in the Quebec harbour is unknown. Quebec was a very busy port, sometimes more than 300 hundred vessels from canoes and rafts to large sailboats sat waiting to be unloaded. This delay was sometimes as long as 3 days. While they waited to leave the ship the Coppings gathered their baggage, sorting out and discarding items no longer useful.

Any provisions remaining, such as oatmeal, potatoes, were set aside to sell in the city once they had cleared customs.

Ladies were advised to dress lightly as many were known to faint in the heat from being too tightly laced and heavily dressed.

We do know the Coppings disembarked July 1st. It would be nice to think it was a bright, sunny, day, with the sun sparkling and dancing on the waves around the S. S. Lively as she lay resting at dock ready for disembarkation.

When time came to leave the ship and the passengers went down the gang plank we can imagine the thoughts running through their minds. For most arrivals this was their first visit to Quebec City. There was nothing familiar to them as they made their way onto the dock and through the crowds in this raucous, bustling, port area.

Very few passengers had someone waiting to greet them. Alone in a strange land, fatigued both physically and mentally from the long, arduous sea voyage, not knowing which way to go, who to approach, must have been overwhelming.

Where was the warm welcome they had been assured would be offered to the newcomers by the promotors at home?

Pamphlets and orators had whipped up emigration fever glorifying this new colony but failing to mention any of the shortcomings and challenges they would have to face.

Stories of green fields, picturesque town and villages, and the magnificent port of Quebec waiting for their arrival was promoted by these emigrant chasers. Instead they came upon a dirty, noisy, waterfront where they were shooed here and there by officious strangers often in a language they did not understand.

While there were few to greet the incoming passengers there were many merchants supervising the unloading of cargo from their transport ships bustling about shouting orders and recriminations to the dockhands. Livestock being loaded and unloaded added to the commotion. Braying, neighing, grunting, cackling, resounded through the port area as animals were driven here and there.

Shouts from dock workers were directed to the crowd to make way for their horses and oxen used in loading and unloading every sort of goods being transported.

Amidst this turmoil immigrants gathered alongside the vessel they had just left and to see to the unloading of their personal goods. Arrangements for storage or transport were negotiated with waiting agents. Their possessions taken care of, their search for shelter for began.

Among the crowd were shady promoters, waiting to accost their prey like buzzards. These characters used charm and wile to prize moneys from unsuspecting individuals, offering them services such as finding shelter, employment and land for large fees before disappearing into the crowd.

For those who managed to avoid getting embroiled with these questionable characters reliable services and information could be obtained at government offices for free. These services included advice on all aspects of settlement. Representatives could advise the colonist on seeking work, land grants, even where they might find storage, shelter, and travel arrangements.

Government agents not only cautioned against unscrupulous agents, they also warned against imbibing too freely of the plentiful, cheap liquor available. It is easy to imagine a good, strong, drink being very tempting. The reality of the situation they faced was often far from what they had been led to expect by over zealous or ignorant recruitment officers. Many were ill prepared mentally and physically for this adventure, yet they did not have the means to turn back. A good example of this is the Moody sisters, Susannah Trail and Catherine Parr. Their families faced unimaginable, well documented, hardships mostly due to ignorance, and lacking suitability to life in the wilds, resulting in poor decisions being taken on their part.

In a letter written to his brother Thomas Ridout described the port and city of Quebec on the very day the Coppings arrived. “There are near 200 sail lying in the river, they form a forest of three or four deep for six miles. Consider what the loading and unloading of 200 sail must make. The quays and lower streets are covered with bales and men. One half of the cruise of ships looked to be made up of boys between nine and 14 years old, nice, smart little fellows.

There are great works going on now, round towers and half moons are building in front of all the gates, in the double wall is continued down through the Quebec suburbs. They are in great expectations here of war with the Yankees, and the works are accordingly carry that with great industry. There are two or three additional regiments expected from England.

The market is well supplied with everything, especially strawberries, nice, fresh butter on leaves, gooseberries pancakes of all kinds. Better mutton and beef that found in Montreal.”

Ahhh, but there was much to learn in this new classless society, not all easy to accept by those brought up in a country with traditions going back hundreds of years.

The servant – employee relationship was much different in the colonies. The customary deference of servant to master was totally lacking in the New World. Workers rubbed shoulders with their employers freely without any hint of the objection so ingrained in the world they had just left.

They even sat down to the table with the family, something unheard of in Britain. Any slight, real or imagined, was seen as cause to leave. Unlike at home, another position was easily found as there was no job shortage in this new colony.

There was also adjustment, both mentally and physically, to the extremes of weather, hot and cold. British settlers had the advantage of the experience of the French colonists 200 year occupation. The wiser ones took notice of their experience and followed suit. This said, the new comers still had much to learn.

The Coppings arrived in Quebec City at the height of the summer season. The heat and humidity at this time was unlike anything they had experienced in England. Layers of heavy woollen materials suitable for wear when they left home in early May in Europe and on shipboard crossing the Atlantic were very uncomfortable in the summer heat. Combined with the humidity of Quebec City, it would take time for their wardrobe and bodies to adjust.

Then came winter, a bone chilling experience for the Europeans that caught many by surprise. Here winter started much earlier than they were accustomed to. Lakes and rivers began freezing in October. Snow quickly followed. High winds swept the snow into great drifts. This white, frozen world continued into March and even April.

Many stories, both real and exaggerated were told of the cold in Quebec.

…..in less than an hour a pail of water was frozen solid

…..milk was frozen solid in blocks and taken to market in bags or sacks

…..the price of the blocks were marked with a nail or knife

…..unfinished tumblers of brandy and water left on the table overnight became solid ice

…..a person who became lost was likely to freeze to death before he was found

The clothing that had been too warm in the summer was inadequate in the cold of winter. Their habitual winter wear had to be augmented adding extra layers.

Houses required much hotter fires than was customary at home. Water froze in houses despite roaring fires in the hearth.

Wheeled vehicles were replaced by sleighs for winter travel. Snow blindness caused by the sun reflecting on snow was another hazard of winter. The unwary could be blinded for days if they were too long out in the bright sunshine.The Coppings again gave witness to close contact with Canadians even adopting moccasins for winter wear.

The Copping family settled in the Parish of St. Jean on Ile d’Orléans. George was employed as a sawyer at the large Patterson Mills in Montmorency just across the river.

Mr. P Patterson, became the proprietor of the extensive sawmills at Montmorency. One of these mills had 360 saws. The mills were now owned by the estate of the late George Benson Hall, Patterson’s son-in-law.

Peter Patterson, about 1719, left Whitby, England, to seek his fortune in Canada. His skill of the shipbuilder, his integrity of character and business habits, later on as a partner in the wealthy Baltic firm of London merchants who had representatives in the colony. At the time of Napoleon’s Continental blockade, the English government, seeing that the Baltic was closed for the supply of timber for the Navy, gave out a large contract to Mr.’s Henry and John Osborne for masts and oak. This company employed Mr. Patterson to dress and ship this timber. A timber license, of portentous import, authorizing the cutting of oak and masts for the Navy in all British North America was issued. Under authority of this license Mr. Patterson partly denuded the shores of Lake Champlain as well as the Thousand Islands of their fine oak. Mr. Patterson was the first to float oak logs into Quebec. He built a large mill at Montmorency that soon attained great importance in the area.

During their five year stay in the Quebec City area, two more children were added to the family. Their first daughter, Clarinda was born December 28, 1812. Two years later, April 13, 1814, a fifth son, James, was added to the family.

Ironically, after having been subjected to the effects of the Napoleonic War in England, not quite a year after they arrived in Quebec City rebels from the United States invaded the Canadas.

For reasons unknown, the Coppings decided to move on upstream to Montreal. While in Quebec or earlier, George made the acquaintance of David Petrie Sr., an ex military man, and his family who had land in Rawdon.

Another friend, John Eveleigh, who was in the leather business in Montreal, also had a lot in Rawdon near

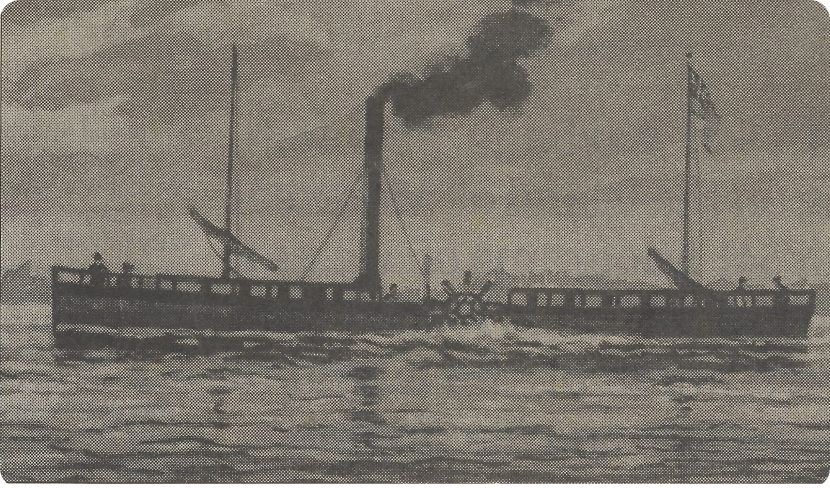

The Accommodation

This sketch was made in 1942 from a description of the Accommodation

There were two options for travelling between Quebec City and Montreal. The first and oldest was by coach. Well made and kept in good condition, the road from Quebec City to Montreal ran along the north shore of the St.Lawrence River. A chain of farm houses, mostly less than a hundred yards from the other offered passer-byes good food and comfortable quarters for the night as well as fodder and stabling for the horses. It was a long, arduous journey taking several days.

A second, and more recent option was the river route. Steam boats transported people and goods up and down the St Lawrence River on a regular schedule. The 180 mile trip took 24 to 30 hours. Provisions, although not particularly generous, were supplied on board.