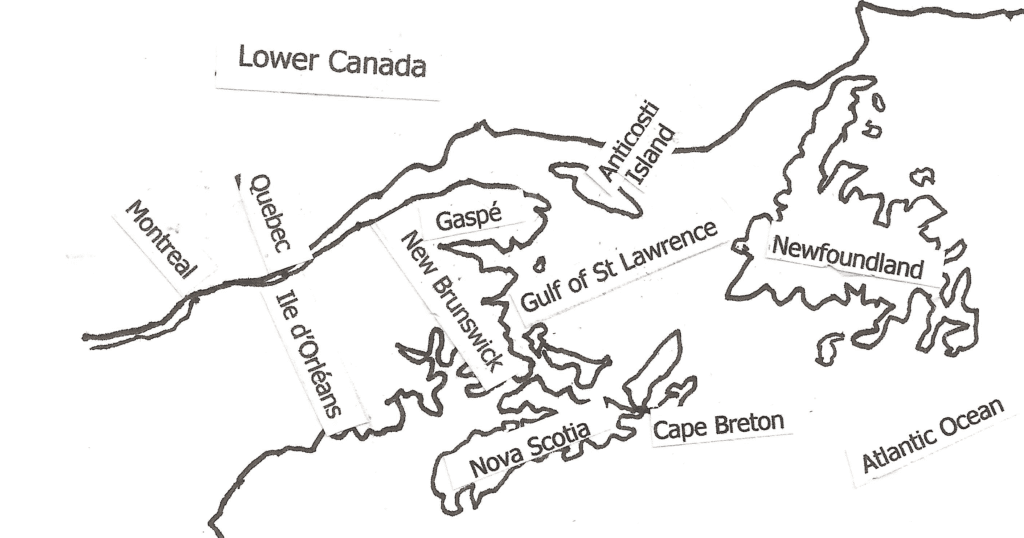

Crossing the Pond and Beyond

A Typical Early Sailing Vessel

George was always one to take on responsibilities, a natural leader, a community man. Fellow passengers looked to George to settle the little disputes and grievances that arose on the long passage George was also a firm believer in Church and held regular Sunday services for the passengers and crew. Elizabeth was also ready to give a hand. When there was illness, despite having her own four babies to look after, she was pressed upon to give help to fellow passengers. Not having any physical proof, only family tradition, I cannot vouch for the happenings at sea, but this is what I was told by my grandfather and other members of the family and from what we do know of his activities in later years, this would seem quite plausible.

The journey across the Atlantic was a formidable undertaking for the Coppings family. Typically, lasting 6 to 12 weeks, the duration depended heavily on weather conditions and the state of the ship.

Early sailing vessels were often cramped and overcrowded, becoming a temporary home for hundreds of passengers. The ship’s log meticulously recorded the names, ages, and origins of steerage passengers, as the captain was only compensated by the government or sponsor of the immigrants for the safe arrival of live passengers.

The experience was isolating and harrowing, best captured by lines from The Ancient Mariner describes the experience:

Alone, alone, all, all, alone. Alone on a wide, wide sea.

The risks were numerous, including storms, rough seas, and even shipwrecks, making the crossing a perilous endeavour.

The voyage across the Atlantic typically spanned from 6 to 12 weeks, with its duration heavily dependent on unpredictable weather patterns and the condition of the ship. Travellers endured this challenging passage, facing the uncertainty of the sea, as every aspect of the journey was dictated by the whims of nature.

The ship’s log was required to enter the name, age, and origin of steerage passengers. This was done faithfully as the government or sponsor of the immigrants only paid the captain for the safe arrival of live passengers.

Cabin passengers who paid their own way were not necessarily recorded in the ship’s log.

Although the Coppings would have been cabin passengers, they were still facing a minimum of six weeks on board a crowded ship with little privacy and totally lacking in facilities. They would have had to bring, as well as all the requirements to start a new life, their own food, water, medication and anything else that might be needed on the crossing.It is known that George was an avid reader and had a large collection of books. Family lore has it that he brought his books with him.

It is highly likely that he and possibly even his wife read Heriot’s account of ‘The Canadas’. Was this what prompted them to pack up their four babies and leave family and friends behind to seek a new and hopefully better life far across the ocean? Was it the economical crisis in England? Was it dissatisfaction with the political situation? We can only speculate, his diaries having burnt many years later in a fire that completely destroyed the family home.

George was always one to take on responsibilities, a natural leader, a community man. Fellow passengers looked to George to settle the little disputes and grievances that arose on the long passage George was also a firm believer in Church and held regular Sunday services for the passengers and crew. Elizabeth was also ready to give a hand. When there was illness, despite having her own four babies to look after, she was pressed upon to give help to fellow passengers. Not having any physical proof, only family tradition, I cannot vouch for the happenings at sea, according to my grandfather and other members of the family and from what we know of his activities in later years, this would seem quite plausible.

Having spent eight weeks crossing the Atlantic Ocean, the Lively was finally making its way towards the mouth of the mighty St Lawrence River. As the ship sailed around the southern tip of Newfoundland and into the relatively narrow passage of Cabot Strait that separates Newfoundland and the northern tip of Cape Breton the sight of land must have been very welcome. At this time both islands were still rather sparsely settled and the rocky shores of Newfoundland contrasted greatly with the gentler, greener images of Cape Breton.

Making its way through the Cabot Strait, the Lively entered the Gulf of the St Lawrence and once again there was no land in sight. The joy felt at the first sight of land after being at sea for several weeks was evident, to lose sight of it again so quickly must have been very disappointing.

Unlike on the open seas, land would not be out of sight for long, soon the Magdalen Islands were sighted on the port side. Although there was no farming done on this isolated cluster of small islands a few fishermen and their families had settled and their dwellings would be visible to passing ships.

As the Lively made its way towards the mouth of the St Lawrence the passengers would occassionally be able to catch a glimpse of a distant shore or even small ‘islands’. In reality these were huge rocks jutting out of the water. In early July they would be home to literally thousands of large white sea birds called gannets. They built their nests on the rocks every spring. During the long days of summer they fished in the Gulf waters coming back to nest on the rocks at nightfall.

The view from the deck was very different from anything the passengers would have ever seen in the British Isles. The rocky shores and vast uninhabited land was covered in dense forest unknown in Great Britain.

Sailing in this area was not necessarily without delays. The cold Atlantic waters meeting the warmer waters of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland tended to create dense fog. The shift of the winds determined where and how thick a fog would have to be contended with.

At times the fog was so dense ships were forced to weigh anchor and wait. It could be days before the fog lifted and the ships could continue on. Having finally crossed the Atlantic and once again in sight of land the weary passengers were often greatly frustrated at this delay.

Weighing anchor was not just pitching an anchor overboard. In all it could take six hours to weigh or raise the anchor depending on the wind and the length of the cable required.

The procedure was a long, laborious task, taking four or more hours and involving several sailors manning the ropes and pulleys to ease the anchor down.

Raising the anchor was the same procedure in reverse.

If the wind was favourable the captain moved the ship to a vertical point over the anchor. Once the anchor was cleared of the water it had to be handled very carefully so as not to damage the ship which was lashed to the forecastle. The huge cable was stored on the deck below the water line.

The cable was made of soft manila rope. When it dried it was used as a mattress for the senior office

Another distraction in this area was the sight of other ships, some heading across the Atlantic, some going upriver as they were. On approaching another vessel the ship’s flag was raised to identify its self.

One can only imagine the excitement created by the sight of land and fellow humans in the many fishing boats that passed close enough to exchange greetings and news.

Often times captains would recognize an acquaintance’s flag and the ship would heave to near enough to shout greetings and exchange news. To people who had been at sea for one or two long months contact with other human beings was a great relief.

After making its way slowly through the Cabot Strait the ship proceeded towards Cape Ray and Cape North where the Isle of St. Paul, actually a huge rock rising from the water, divided to form three conical peaks.

The water on either side of the island was deep enough for ships to pass through but currents and rocks made passage very difficult resulting in many shipwrecks in this area.

Remnants of these disasters, including human bones, were visible to those on board passing ships. Not a very inspiring site.

Continuing towards the mouth of the St Lawrence the monotony of life on board would occasionally be broken by a glimpse of a distant shore or even small ‘islands’ that were in reality huge rocks jutting out of the water.

During the summer months the rocks were home to thousands of large white sea birds called gannets. Here they built their nests every spring and spent the summer fishing in the Gulf waters coming back to nest on the rocks at nightfall.

Smaller birds would entertain the passengers following ships crying for bits of food to be thrown away. Incoming ships would be poor pickings compared to those heading out but the birds were ever hopeful as they flew and squawked behind the ship.

The ship sailed towards the entrance to the relatively narrow 42 mile passage of Cabot Strait that separated Newfoundland and the northern tip of Cape Breton.

At this time Newfoundland and Cape Breton were both sparsely populated. Passengers stood on the deck gazing hungrily at the sight of land. The rocky shores of Newfoundland’s rugged coastline contrasted so greatly with the gentler, greener, images of Cape Breton on the opposite shore.

Miramachi, on the shore of what became New Brunswick, on a clear day could have been visible from the deck of passing boats.

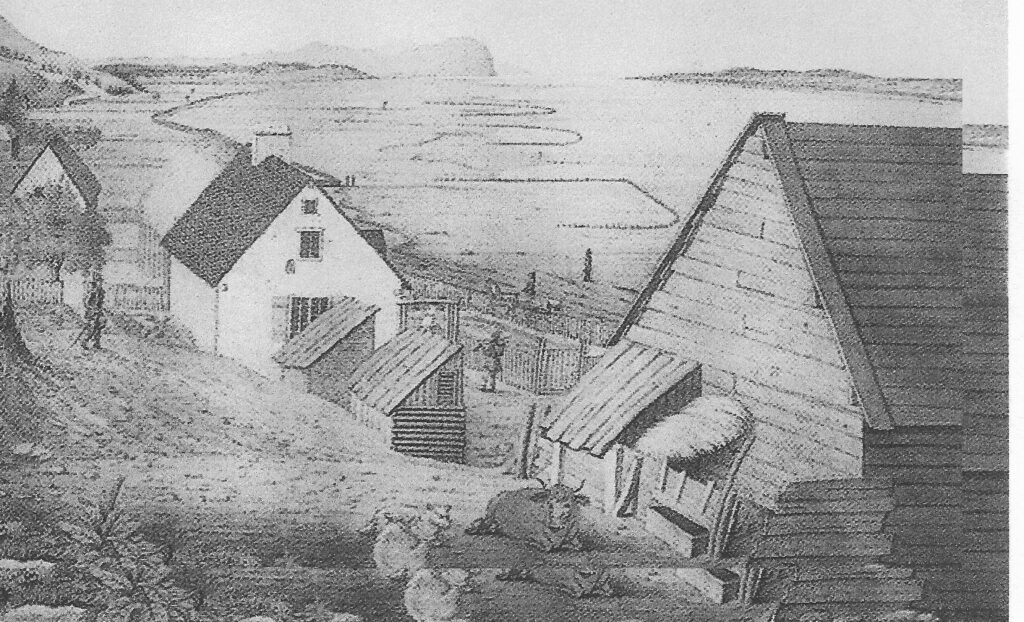

Although this might seem a very primitive settlement, when the Coppings sailed past in 1811 the Miramichi had been settled by Europeans for 163 years. The Mi’kmaq nation had long been in the area previous to the arrival of the French.

Although this might seem a very primitive settlement, when the earliest settlers were coming to the Rawdon Township, the Miramichi had already been settled by Europeans for 163 years.

After the Treaty of Paris, 1765 – 1800 many Scottish immigrants settled in Miramichi. Irish immigrants began arriving in 1815.

Ship building and the export of lumber dated back to 1765. This industry suffered greatly when steel hulled ships replaced wooden hulls, as well as when over cutting of the white pine greatly depleted the forests.

The great fire of 1825 was the final blow to this production.

The Gulf of the St. Lawrence River

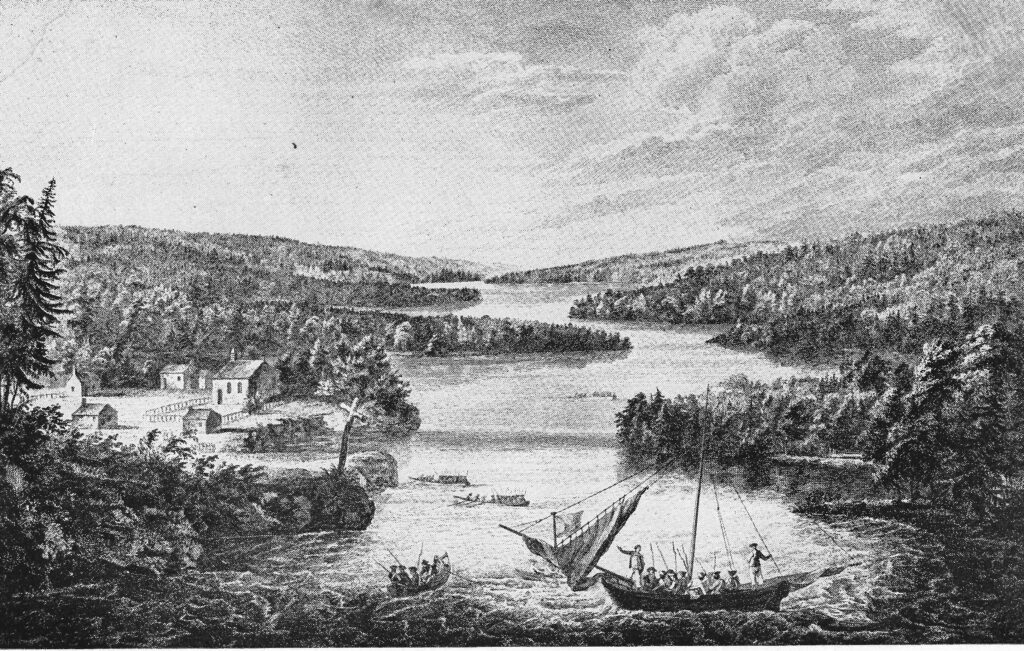

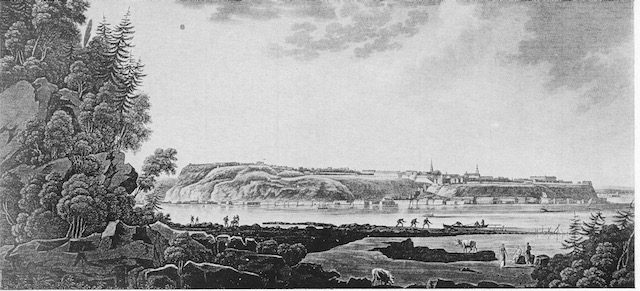

This sketch was drawn from on board ship during Wolfe’s approach to Quebec City.

Sailing through this seemingly unending expanse of water to gain entrance to the St. Lawrence River was almost beyond the scope of the imagination of the ships passengers, yet there was still much more to come.

New arrivals could not visualize the size of the waterway they were entering. Rivers in the British Isles were merely creeks in comparison to the St. Lawrence River.

In places the gulf reached 42 miles across and it was a 180 mile sail on the river to their destination of Quebec. In ideal conditions the sail up the sail up the river took 8 days, the return trip was 5 days. However conditions were not always ideal.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence, the largest estuary in the world, stretching 2000 miles (3,218 km) to its source in Minnesota, is the greatest tidal water river in the world.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence is 90 miles wide (approx. 145 km.) at the entrance. It was like being on the ocean again, nothing but water in view.

Despite this seemingly open space, guiding the ship safely through the waves was a precise and frequently challenging operation.

Many challenges faced the captain if he wished to deliver his passengers up the river to Quebec safely.

Unavoidable delays due to storms or calms were frequent.

Wild, stormy, weather, with little or no warning swamped ships, sometimes blowing the ships back towards the Gulf.

Where the river was particularly treacherous special pilots had to be taken aboard to guide the ships through these channels. If a pilot was not available the ship lay at anchor to wait for his return. (In rough weather pilots on ships sailing back to Europe were sometimes obliged to stay on board until the ship docked in Europe where they boarded the first ship going back to Quebec.)

The seamen on these Atlantic crossings, many having made several trips, were well versed on the sights along the river and were known to be very enthusiastic tour guides pointing out the landmarks as their vessel proceeded towards Quebec City.

It was about 90 miles (145k) from the tip of the Gaspé to the nearest shore of Anticosti island. There were no permanent residence on the island. In winter the aboriginals hunted although none actually lived there.

If the winds were favourable this trajectory of the Gulf of St Lawrence to the mouth of the river would take about twenty-four hours although bad weather could delay the progress for several days.

The Gaspé not only had fishermen settled along its banks but there were shipyards scattered along the coast, as well. In 1807 George Heriot reported 300 families, mostly Roman Catholic, settled in this area.

The Lively continued on, the shores of the Gaspé Peninsula drawing ever nearer as they slipped past the south side of Anticosti Island which divided the entrance to the mighty St Lawrence River. The south channel was used by the ships as it was wider and better sailing than the northern channel. Here it is about 90 miles across between Cap Rosier on the tip of the Gaspé and the nearest shores of Anticosti Island.

Anticosti Island was uninhabited at this time. In winter it was used by a native tribe for hunting but none actually lived there.

If the winds were favourable this trajectory of the Gulf of St Lawrence to the mouth of the river would take about twenty four hours, although bad weather could delay the progress for days.

The Gaspé not only had fishermen settled along its banks but there were shipyards scattered along the coast, as well. In 1807 George Heriot reported 300 families, mostly Roman Catholic, settled in this area.

The Gaspé not only had fishermen settled along its banks but there were shipyards scattered along the coast, as well. In 1807 George Heriot reported 300 families, mostly Roman Catholic, settled in this area.

It was about 90 miles (145k) from the tip of the Gaspé to the nearest shore of Anticosti island. There were no permanent residence on the island. In winter the aboriginals hunted although none actually lived there.

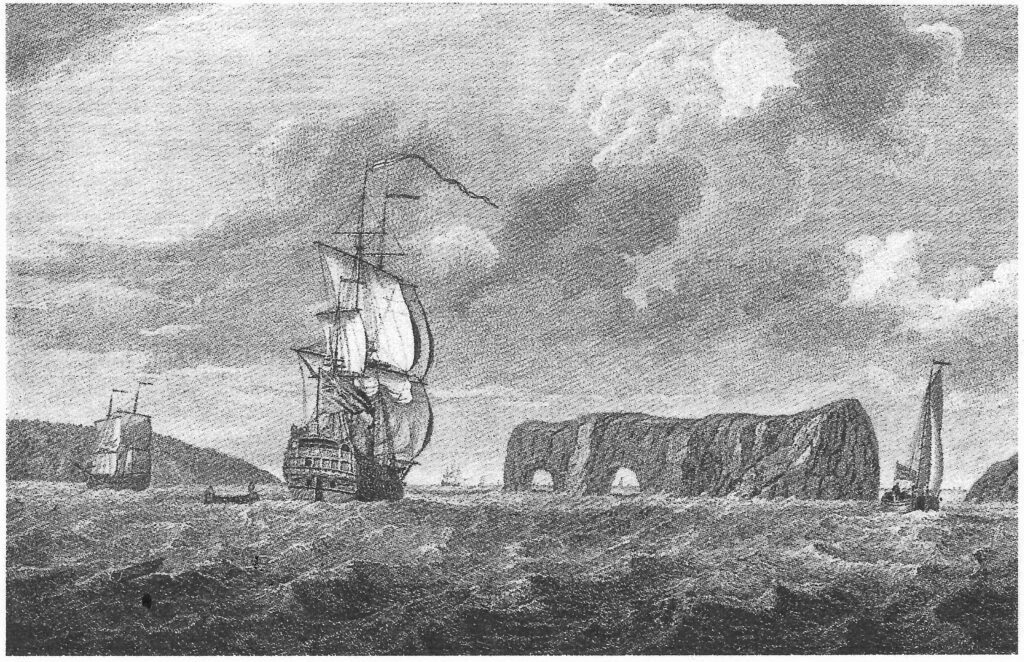

This is the earliest known sketch of the Rock. The sailing ship is the Vangard under the command of Robert Swanton. The Vangard had 64 guns and was instrumental in raising the seige of Quebec in 1760.

Ships sailed near enough to this already well known phenomenon for passengers to catch a good view of Perce Rock which jutted out into the Gulf. Its majestic appearance with the intriguing holes were the subject of many articles on travel as well as seen in paintings and drawings. In 1607 Samuel de Champlain, the first known European to see this rock, had described it in his log a hundred years earlier.

Here the entrance to the St Lawrence River is divided into two channels. The south channel was the preferred choice as it was wider and offered a better route and better sailing than the northern channel.

On the shores of the Gaspé Peninsula, four hundred miles from Quebec City, the sailboat slipped past the south side of Anticosti Island which divided the entrance to the St Lawrence River.

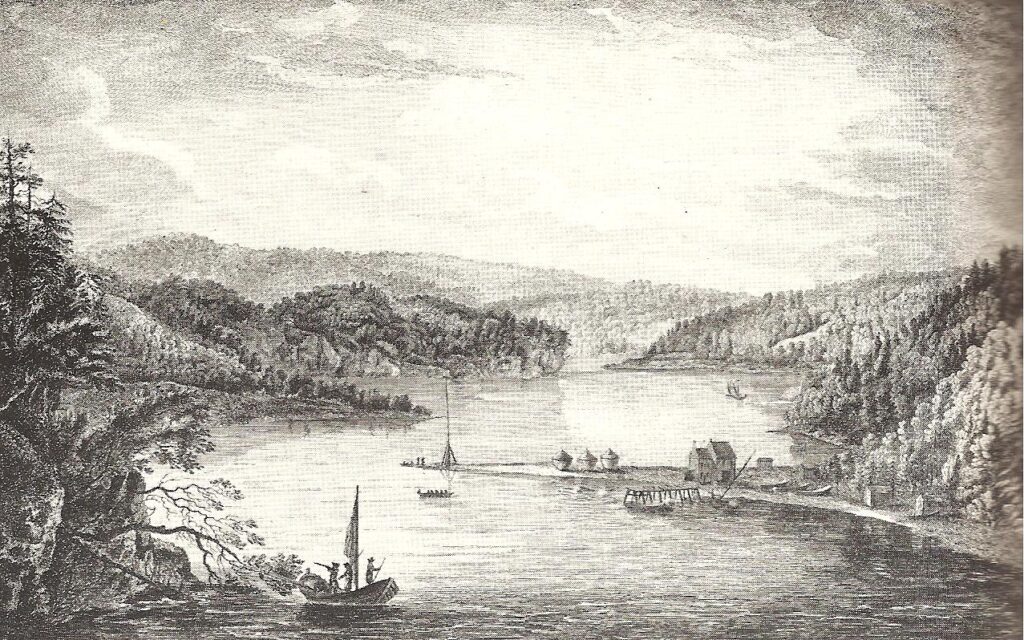

The St. Lawrence River

The S.S. Lively, finally sailing in the mighty St. Lawrence River, still had another 400 miles to go before arriving at Quebec City. The trip up the the river could take as much as two weeks. For passengers where such great distances were unthinkable many might wonder if their voyage would ever finish.

The current often negated the wind power and sudden storms and violent wind squalls tended to cause frequent delays. At times sail boats were completely stilled, at other times the wind was so ferocious they had to weigh anchor to avoid being thrust upon the rocks or islands that dotted the river. In certain places, due to narrow passages, hidden rocks, fickle shoals, or devilish currents, captains of vessels going upstream were required to take on special pilots to guide them through the water.

However, as the river gradually narrowed the passengers would now be able to spot the shoreline from both sides of the ship. And what a view it was! Thick green forests covering the mountains and coming down to meet the river as it flowed past, sparkling and dancing on sunny days, or dark and threatening in foul weather.

There was little or no settlement on the banks of the lower St Lawrence but as the river continued to narrow and the effect of the Saguenay River came rushing into the St Lawrence was felt, small settlements came into view, particularly on the north shore due the fur trade or fishing.

Miramachi, on the shore of what became New Brunswick on a clear day was visible from the deck of a passing boat.

The Mi’kmaq nation had long been in the area previous to the arrival of the French.

Although this might seem a very primitive settlement, when the earliest settlers were coming to the Rawdon Township, the Miramichi had already been settled by Europeans for 163 years.

From 1765 to 1800 many Scottish immigrants settled in Miramichi. Irish immigrants began arriving in 1815.

There was little or no settlement on the banks of the lower St. Lawrence River but as the river continued to narrow and the Saguenay River came rushing into it, small settlements came into view. On the north shore the settlements were mostly to do with the fur trade or fishing. The south shore was spotted with farms running back from the river. There were also a few small shipyards along both coasts. Tadoussac was already established as a harbour for ships and port of entry for the Saguenay River.

There were also a few small shipyards along both coasts. Tadoussac was already established as a harbour for ships and port of entry for the Saguenay River.

At LaMalbaie there was another kind of settlement. Every spring fishermen trapped porpoises to extract the oil that was in great demand. This was a very lucrative business. One could get as much as a barrel of oil from even the smallest porpoise.They also caught seals and sea cows for the fisheries. Rough buildings to house the land operations and work crew of this industry were to be seen scattered around the bay.

Porpoises were still plentiful in 1811 and they would follow the ships on the river, racing and playing around the vessels as they proceeded upstream much to the delight of passengers, especially the younger ones. Sometimes they travelled as far as Ile d’Orleans entertainig the travelers on board ship.

Some forty miles farther upstream Les Eboulements would come into view. They were considered of particular interest and were known to be pointed out by the sailors. These huge masses of rock came jutting out into the sea several hundred feet in height and seemed to stand guard over the river.

On the south shore the little town of Kamarouska nestled on the riverbank. This town with its whitewashed buildings contrasting with the green of the fields and the dark forested mountains rising behind, gave the first promise of real civilisation. The whitewashed farm houses built virtually side by side faced onto the river which was still the main means of travel. In the little village the spire of the church pointed up to the sky. And the village houses and places of business clustered around forming a very compact little town.

From here on, the south shore was settled by farms that grew ever more fertile as the river advanced to the interior. These farms, settled under the French Regime in the Seignorial system, were long and narrow, the fields stretching back a mile or more from the river. The settlers were still mostly of French descent very little having changed in the previous fifty years or so.

Farms were still handed down from father to son. In early July when the Lively was going upstream the view would have been idyllic. The fields would be lush with green grass and grain. The cattle would be seen grazing in the pastures while the farmers and their families worked in the fields and gardens.

A scarce twenty miles further Ile aux Oies lies off the south shore, a little island about seven miles long and three miles at its widest. As the name indicates, this was a nesting place for wild geese whose activities could be seen from on board ship. The sight of thousands of these magnificent white birds flying and honking as they went about their business was a very impressive sight indeed.

Here there was a settlement of about thirty families. These settlers lived off the land, logging, farming, and fishing. The buildings and fields of this island would have been visible from the ship’s deck.

Gradually the St. Lawrence River loses its salt as the river penetrates further inland the water becomes fresh.

A little further upriver at La Traverse was considered the most hazardous part of the journey. A local pilot had to be taken on board to guide the ship. This could delay the arrival at Quebec City for a few hours or even a day, depending on the availability of a pilot.

A little farther on Ile au Coude sits just off the north shore. This little island is only about seven miles long and three miles at its widest. It had a settlement of about thirty families at that time. These settlers lived off the land, logging, farming and fishing. The buildings and fields of this island would have been easily visible from the ship’s deck.

Here the St Lawrence starts to lose its salt and the water becomes fresher as you continue inland.

A scarce twenty miles further Ile aux Oies lies off the south shore, a little island about seven miles long and three miles at its widest. As the name indicates, this was a nesting place for wild geese whose activities could be seen from on board ship. The sight of thousands of these magnificent white birds flying and honking as they went about their business was a very impressive sight indeed.

Here there was a settlement of about thirty families. These settlers lived off the land, logging, farming, and fishing. The buildings and fields of this island would have been visible from the ship’s deck.

Gradually the St. Lawrence River loses its salt as the river penetrates further inland the water becomes fresh.

A little further upriver at La Traverse was considered the most hazardous part of the journey. A local pilot had to be taken on board to guide the ship. This could delay the arrival at Quebec City for a few hours or even a day, depending on the availability of a pilot.

Ile d’Orleans presented a picturesque view rising from steep banks in some places, a more gradual ascent in others. It was divided into five parishes, St. Pierre and Ste. Famille on the north, St. Francis, St. John, and St. Laurent on the south. About 2000 people lived on the island.

Typical of the French settlements, the farms were on narrow lots with houses sitting relatively to the other facing along the waterfront. While a few stone houses were built, the majority of homes on the island were constructed of wood.

Ile d’Orléans was one of the earliest and most densely populated settlements in New France. It was also the most fertile area providing food for Quebec City and the surrounding area.

While Ile d’Orleans was known as the breadbasket of the Quebec City area, surrounded by water, it also profited from the river’s bounty. Eel traps are seen in the sketch set out along the shore.

Most of the farmers on the island were descendants of the original owners. Today this is still true.

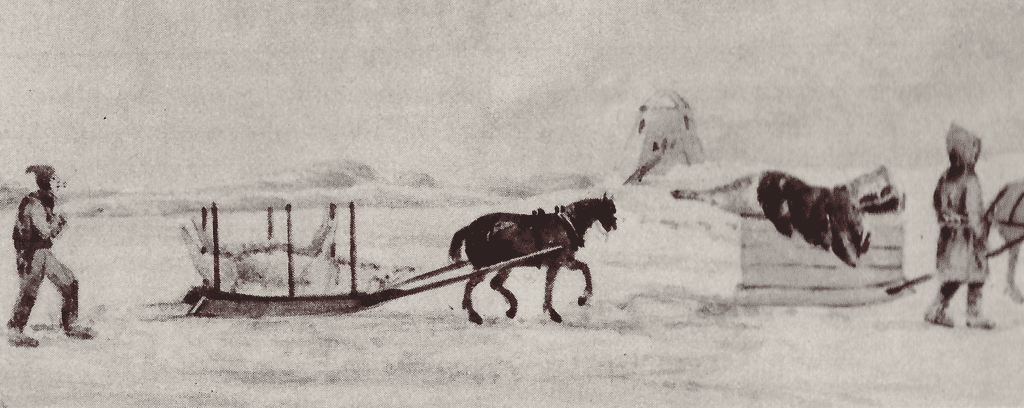

During the winter months when the river was frozen they crossed on what was called the “pont”.

A few years earlier, for two consecutive years, a plague of grasshoppers had ravished the island but when the Coppings arrived in 1811 it was once again thriving and supplying the Quebec City region with its produce.

The Copping family settled in the parish of St. Jean. George found employment in a sawmill across the river from Ile d’Orleans.

A View of Quebec From Point Levis George Heriot

As ships sailed into the Quebec harbour the first view of Quebec from on board ship would have appeared much like this sketch by George Heriot.

In 1811 Quebec City, although it could not boast to be old in comparison to European cities, was far from being a new settlement. Founded in 1608, it was second in age only to Louisburg in Nova Scotia. (In 1605 Champlain had left a few men to winter in Louisburg.)

Farmers brought their produce the mile across the river on barge or by boat. During the winter months when the river was frozen they crossed on what was called the “pont”.