The Next Generations

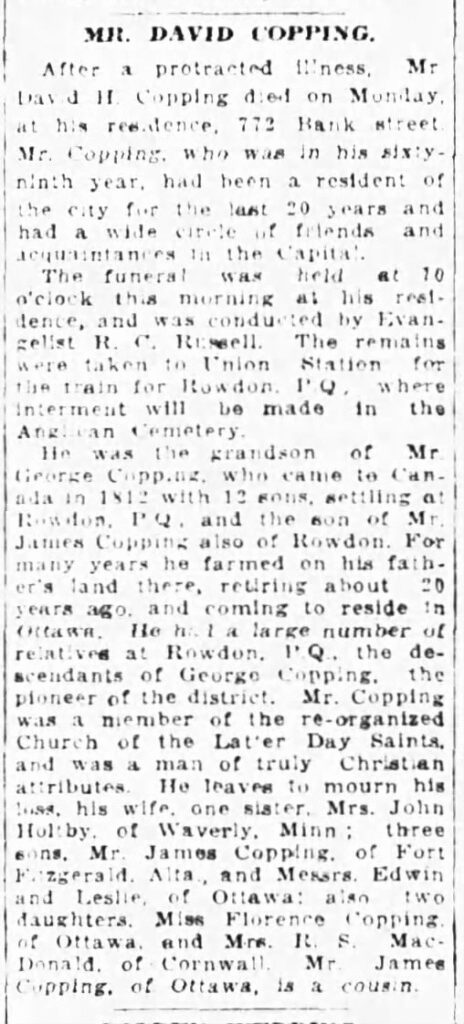

George and Mary

Son George had applied for lot 24 N on the 4th range. With the help of the family the requisite amount of land had been cleared and were soon under cultivation, as well, a house and outbuildings were built. May 23, 1830 he had married Mary Gray, a lass originally from Kilglass, Ireland and they now had three children.

On 23 May 1830 he had married Mary Gray, a girl originally from Kilglass, Ireland, and they now had three children.

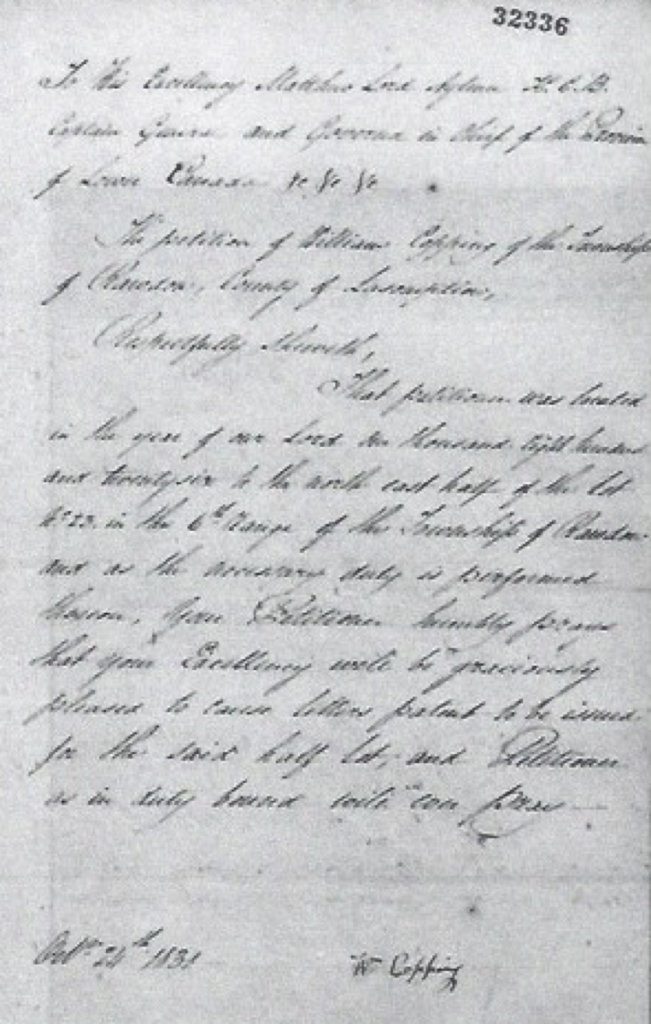

William and Margaret

William’s Land Grant for lot 23 – Range 6, October 24th 1831

April 7, 1833 William married Margaret (Peggy) Gray, a sister to George’s wife, Mary, born 1818 in Kilglass, Ireland.

Peggy was not as robust as her sister, Mary. She was not only very susceptible to the frequent infections that went through the community but also had difficulties during her pregnancies as well as giving birth. Her mother-in-law was frequently called to attend to Peggy or the little ones. Young Mary went over when longer nursing was required.

Fortunately Peggy also had help in the house to take over while she was confined to bed. Her father-in-law, George frequently referred to “Peggy and her maid” being at the house. At this time until newly weds had offspring old enough to help in the house help was hired. The help was often a young girl or a lady, widow, etc., requiring a source of income.

William was appointed Justice of the Peace which Peggy considered made him a man of importance in the commuinity. They hosted many receptions in their home. For these occasions Mary and Liza were called on to help organize these fashionable affairs.

William was known for his talent as a violinist. He played for dances and as accompianist for his sister, Clarinda. The 1909 article in the Montreal Star describes he and his sister sailing down the river in a dug out boat entertaining the neighbours who rushed out to hear the lovely music. This is definitely artistic license as the Little River, as it was called, would hardly float a child’s paper boat.

For many years William and his brother Henry were inseparable. William’s first child was named not for his father, but for his brother. From the time Henry’s namesake was very young his uncle would take him home to spend a few days at the homestead.

Then a serious argument regarding a potash plant led to a very litigious lawsuit which left the two brothers totally alienated. Two generations later the families remained hostile. Although I was never given an explanation I recognized that certain members of the family were not recognized.

William and Mary had 13 children,

Henry born 16 March 1834

William born 28 October 1835

Elizabeth (Lizzie) born 1836

(Recorded in George’s Journal)July 14, 1837

Peggy gave birth to a son who died a few hours later. The next day William and Henry took the baby to be buried. This would have been in the school/church on Forest Road.

George born 4 June 1838. In his Journal George reported as the baby was not very well. June the baby was reported as having small pox. July 5 the baby was christened. Thomas, Henry and Mary stood for the child. Despite all the problems George survived.

William born 28 October, 1835

George born June 4, 1838

Elizabeth 2 October, 1840

James born 26 June 1842

Thomas (Captain) born 21 January 1844

John born about 1847

Joseph 13 January 1849

William (Winnie) born 23 September 1845

William Copping’s house was on Rue Arthémise (today rue St-Thomas), a short distance from his sawmill.

In 1911 agroup of local citizens created a business for metalwork on Alice Street in the south part of Joliette kown as Flamand Village. Members of this Peoples Foundry included J. Alexandre Guilbault and Ernest Hébert, merchants Ulric Chaputand Jules Laflèche, and broker Alfred Boucher, mechanic Henri Démarais

The Copping’s mill was before the fire that completely destroyed the mill in 1943. The

The mill had by then changed hands, having been acquired by Édouard Gohier.

The Copping sawmill, later the Gohier mill.

For many years after the fire, the ruins of the mill could still be seen on the land between the Château Joliette and the L’Assumption River.

The Kelly family in Joliette were good friends with the William Copping’s. They joined forces to build a sawmill. William Copping bought Skelly out and became the sole owner of the mill until his death.

William was well known and respected in the community. He was appointed an Officer of the Peace, and 27 February 1834 he was elected as a municipal councillor.

Infant born 1837

Samuel Eli born 17 October 1856

Charles born 29 January 1851

Joseph born 13 January 1849

John born 2 April 1847

in photo shows the Copping mill in 1915.

In April Peggy was once again pregnant, and once again she was having difficulty. Mary went over to look after the house. The next day Elizabeth went over and suggested Peggy stay in bed for a few days. For the next three weeks Mary and Eliza alternated staying at William’s whilevery susceptible to the frequent infections that went through the community but also had difficulties during her pregnancies as well as giving birth. Her mother-in-law was frequently called to attend to Peggy or the little ones. Young Mary went over when longer nursing was required.

Fortunately Peggy also had help in the house to take over while she was confined to bed. (George frequently referred to “Peggy and her maid” being at the house.)

Sadly, Peggy lost two babies within 16 months, 5 month old William in 1836 and a newborn son n 1836 William purchased a farm from Hobbs. The farm was already established but further from the homestead, the back corner touched the family farm. A road went past the home farm, over the mountain, and through the middle of William’s farm.

The family was to face yet another loss. William’s wife, Peggy, once again pregnant, was taken sick while over at the homestead. William had to leave her with his parents that night as she was too ill to go home. The next day she seemed to recover enough to leave, but was still far from well. She continued to have difficulties and July 14 Elizabeth delivered Peggy of a baby boy. Sadly, the baby was very weak and died within a few hours. This was now two little boys lost in a very short time and Peggy was slow to recover. During the next few days Elizabeth was over several times to help and encourage her daughter-in-law.

Happily, almost year later, June 8, 1838, Peggy was safely delivered of another baby, a healthy son, christened George.

The new farm seemed to bring no end of problems for William and his neighbours. George was called to arbitrate several times, not always successfully.

William, was said to be a talented violinist. This made him very popular at parties.William, was said to be a talented violinist. This made him very popular at parties.

Certainly, he and his wife, Margaret, enjoyed entertaining receiving 30 or 40 people in their home. His sisters Eliza and Mary, as well as his mother went over to help Peggy prepare for these receptions.

William became a councillor for the Municipality of Rawdon, and a Justice of the Peace.

Elizabeth visited regularly. Happily, October 2 brought a healthy daughter, Elizabeth, into the family.

William and Peggy were also now quite comfortable on their farm on what is now Lake Morgan Road.

Charles and Emma Bennet

Charles, apprenticed to a leather merchant when the family left Montreal did not return to the fold in Rawdon. He married the daughter of a cobbler and moved to New York State where he opened his own shop. Apparently they had 3 girls, Helen born 1842, Anna born 1845, Emily born 1849 and a boy, Charles born in 1855. All births were registered in New York.

George kept in touch with his son via mail and ordered his boots made and sent to Rawdon. There is no record of exchanges between Charles and his siblings.

After the death of their parents, the family lost all contact with Charles. This is understandable as he had been separated from the family at a very early age. George had kept in contact with his son over the years but after his death the thread was lost. Even today Charles descendants continue to be elusive.

John and Julie Dugas

John & Julie’s House in St Ligouri de Montcalm

John is seated on the porch in his rocking chair.

In early October preparations for a celebration were being made. Son John, who had been apprenticed to Philemon Dugas shortly after the family arrived in the township, was to marry Philemon’s oldest daughter, Julie.

John had been living with the Dugas family for several years during which time the Dugas children and their mother had been baptized in the Catholic Church. Over the years John had attended school and church with the family so it is not hard to understand he also joined the Catholic Church before he was married. What is surprising is the lack of reaction from his father. The close relations between the two families were not at all jeopardized.

Due to her father’s standing in the community the wedding was a rather elaborate affair. Elizabeth went down to Dugas’ for a few days to give a hand with the preparations. George joined her on the wedding day. Celebrations went on through the night and it was the next day before they returned home – bringing a couple bushels of flour with them.

Clarinda Edward Rhinehardt, John Jones

The marriage of the oldest daughter, twenty three year old Clarinda, caused trouble in the family. George’s was greatly disturbed at news that she had married their neighbour, Edward Reinhardt November 3, 1835 at St Andrews Presbyterian Church in Montreal. By the time the father found out it was too late to change anything. At twenty three she was free to marry the man of her choice without his consent. The newly weds took up residence on Edward’s farm, lot 20 on the 5th range, just a short distance from the Copping homestead.

James and Florella Wright

Although the family enjoyed a party, James often partyed a little too much. At the break of dawn they all trudged home from a night of pleasure. His brothers picked up their axes and went off to the bush, James took a big head up to his bed.

James was involved in arranging the local militia balls which were always very popular. Yes, James liked having a good time.

The minister, Mr. Reid had purchased a lot in Rawdon” Now that he was leaving George took the opportunity to purchase this land, 100 acres, four acres cleared and close to the homestead. Son George, William and Henry had their own places, this time the deeds were turned over to James.

When it came to marriage James was the only son who did not follow the example set by his older brothers. He was the only boy not to marry a local girl. He chose a bride from Montreal. It is not known how they met only that James seemed to become particularly interested in making the monthly trip to Montreal. As it was never advisable to travel alone a friend of friends James sometimes accompanied him rather than a brother.

The First Book of Coppings written by Wilfrid Copping

Several years ago I received a copy of a booklet called The First book of Copping very kindly sent to me by Wilfred Leslie Copping a fifth generation of the Rawdon Coppings. He was the great grandchild of James Copping and Florella Wright. Born in Ottawa May 19,1919 he gives a very interesting and light hearted description of growing up in that time.

Excerpts from The First Book of Copping

I am Wilfred Leslie Copping, son and only child of Leslie William Copping and Catherine Moreland. I was delivered at home in the early afternoon of May 1, 1919, by my paternal grandmother. There was a doctor in attendance but because he was late and my grandmother did most of the work, he charged only five dollars.

I am not sure of my birth place but it was on Seneca Street in Ottawa south. My mother thinks it was either 27 or 29, she can’t remember, nor can I.

Later we moved to a second-floor apartment in an area of Ottawa known as the Glebe. I like this apartment because I could race up and down a long hallway in a pedal powered car my father built for me. But I did not like this apartment because of the heating system. It was fired by a furnace in the kitchen and it was my job to carry the coal up from the basement and return the ashes to street level. That was two flights up and one flight down, compounded by the fact that one bucket of coal seem to produce two buckets of ashes. My allowance for this and other chores was a nickel or maybe even a dime whenever I could prove my need, and my parents had the money. It was the Roaring 20s but not a period of great prosperity in my part of the world.

We acquired our first telephone while we lived in this apartment, our first electric refrigerator, our first radio, (a crystal set my father made using a Quaker Oats container) and our first automobile, a secondhand 1927 Chevrolet two door sedan. I think it cost about $100. A new car cost up to $1000 if memory serves. I do remember exactly the cost of a Harley $365.

When I was about 10 years old we moved back to a house in Ottawa south. I’ll never forget the moving van, a big, old, red and yellow circus wagon pulled by two magnificent Clydesdales. In the 1930s horse drawn vehicles were a common mode of transportation. The milkman and baker made their daily rounds by horsepower. The garbageman made his pick ups with a team. In the winter horses pulled ploughs down the street.

Before we bought our electric refrigerator the ice was delivered by horse and wagon. Emptying the water filled ice pan was another chore of mine.

My maternal grandfather, who owned a grocery store, offered free delivery to his customers. One of my uncles drove the wagon, with me riding shotgun. Sitting high up on that wagon with a box of Cracker Jack given to me for helping out, I was on top of the world. Great prizes were to be discovered in the bottom of those crackerjack boxes. Once I came across the most magnificent jack knive I had ever seen, a jack knife a Boy Scout would kill for. I always suspected it had been planted by my grandfather, who love to do nice things but hated to be caught at it.

Automobiles were rare in those days. One parked on the street always attract a crowd of admiring on lockers, especially if the car was a Packard, Nash, Hudson, Cord, LaSalle, Studebaker, or Stanley Steamer. But even a Ford, Chevy, or Essex would get attention. When the occasional airplane was heard overhead people would stop and look up until it was out of sight and sound.

The Ottawa Airport was a dusty old field with a single hangar. For $2.00 you could buy a 30 minute flight over the city but you had to sign a release first. I paid out the first $20 I had ever earned to fly a rickety, open cockpit, cloth covered, biplane owned by a neighbour who, in addition to being a pilot and instructor, drove a taxi and ran a fish and chip shop. He made deliveries in a Harley with me in the side car holding the fish and chips. I was never sure whether I was in the Harley or the airplane, he operated them both in the same manner.

My parents knew about the Harley and the fish and chips but they never found out about the airplane. I don’t know what would’ve horrified the more, the fact that I squander $20 on such a reckless venture or that I ever had $20 in the first place.

Charles Lindbergh and his Flying Circus came to our fair city shortly after the solo Atlantic crossing that made him famous. Tragedy struck when one plane got too close to another and chopped off its tail. The pilot jumped but his parachute failed. His machine crashed close to where my father and I were standing and a wheel rolled right up to my feet. The pilot’s name, I remember it was Johnson. My father then worked for a firm that built airplanes. The company had one of the airplanes on display and there was going to be a reception which my father and I were due to attend and hopefully meet Mr. Lindbergh. The accident cancelled out the festivities. It was one of the major disappointments of my young life. Flying in airplanes had a magic for us kids in those early days of aviation the far exceeded space age glamour. In our minds, no more could ever accomplish anything to equal Lindbergh’s feat. So far no one has.

Looking back I think the most interesting aspect of my school day is how they compare to the years that soon followed. In my day, everyone received a good, basic education: reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, chemistry, literature, English composition.

We had a shop twice a week where we learned to handle basic tools. The girls learned how to cook and sew. Students who couldn’t handle regular high school went to commercial or technical schools where they learned something there.

There was discipline. Teachers were in command and everyone respected their authority. We observe the rules and kept out of trouble. I never knew a drop out. I never knew a student to be expelled. Everyone went to school until I graduated, the ground and it took some longer to graduate than others.

A few older kids smoked, but never in school. Alcohol was rare, even among adults. Drugs were unheard of. We learned about opium dens from dime novels. Sex was something you read about and thought about but didn’t do much about. Guys who hung out with girls werte sissies. We were all too busy doing guy stuff. All of which might account for the fact the teenage pregnancy was unheard of and the high school had an enrolment of close to 1000. Oh, there was a scant scent of scandal once when a young male teacher became engaged to one of his students immediately after her graduation. People weren’t sure if that was right and proper considering the preliminaries that must have preceded the engagement. The couple was monitored carefully for at least nine months months by socially responsible neighbours who finally lost interest when they found nothing unseemly to report.

My good old days in the “Good Old Summertime”, at least, were spent at a resort called Norway Bay up the Ottawa River about 40 miles from home. It was called Norway Bay because the area was covered with a dense growth of Norway pine. I loved that place. To this day every time I smell a pine tree I’m 10 years old.

To get to the Bay we took off at the crack of dawn and it seemed like a long way to our destination. The roads were not conducive to high-speed travel; they were gravel, washboard horrors that threaten to shake apart any car that even approached the 35 mile an hour speed limit. So we crawled along. I think we averaged about one flat per trip. Tires didn’t give a good wear then. That’s why everybody carried a couple of spare tires and an air pump.

On the way to and from Norway Bay we’d always stop at some farm for supplies. The quality was better, the price lower and we could haggle. Eggs generally went for $.10 a dozen, fresh from the nest. Jersey cream so thick it would hardly pour from the bottle, $.25 a quart. Chickens and ducks went for $.75 each and bread, hot from the oven $.10 a loaf. An arm full of fresh vegetables was always thrown in for good measure and we could help ourselves to all the apples we cared to pick. A lot of socializing was also included. My father and the farmer would settle the affairs of state, my mother would woman talk with the farmers wife and I would mingle with any young’uns who happened to be around. They were generally several of both sexes and let me tell you, those big awkward farmers could produce some mighty pretty daughters.

So we completed, in the best part of the day, a trip that now could take less than an hour.

Cottages at Norway Bay, like cottages everywhere, were simple pine plank affairs painted on the outside, unfinished on the inside. The porch stood at the front of each cottage where we sat watching the neighbours. A screened in porch along the side served as a mess hall and bunkhouse. Under the cottage with space for boats, rafts, fishing rods, porcupines, sleeping dogs and the occasional skunk.

There were no paved roads, electricity, running water, or modern plumbing at Norway Bay in those days. We used candles and kerosine for illumination, cooking was done over a wood stove. Water was pumped by hand from a well. A back house always stood close by.

Every Saturday night there was a movie or a dance at the local hotel which had the only electricity in the area. The power came from an old donkey engine and generator held together by 20 feet of leather belting. The erratic put,put, put-put-put, of that donkey engine blended with the whippoorwills to create the most soothing lullaby in the world. Put-put-put you right to sleep.

In winter we were busy with school, homework and chores. Weekends my buddies and I would go skiing or play hockey. I can remember Donning my equipment early on a Saturday morning and not taking it off until I got home for dinner that night. We had lunch only if we had the foresight to pack a sandwich in her pocket, an inside pocket. Anything in an outside pocket would be matched with snow and frozen stiff.

On school nights, as we got older, we would go skating. It was free. It got us out of the house. And it was a great way to meet new girls.

Going to the movies was a big event in the 1930s. I can still remember when the talkies and colour were introduced. Radio also provided good entertainment. TV had not yet been invented. I saw my first set at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

For a $.10 matinee or a $.35 evening performance the local movie house provided a program consisting of a comedy short, a cartoon, a documentary of some kind, news of the week, a B-movie, and finally the main feature. On Saturday afternoon the audience was treated to yet another episode of serialized cliffhanger, generally a western. There was no snack bar. You brought your own goodies.

The whole show lasted three hours, easily. To help boost attendance during those depression years, a piece of dinnerware or “silverware” was giving away one night each week. Over the course of a long winter a family could assemble a respectable set of each. When highly treasured pieces were offered such as a gravy boat or a serving spoon, the line at the office box office went halfway around the block.

Lily Isabella Copping and Robert McDonald as written by her nephew Wilfrid Copping

1892 to 1964

My father, David Henry Copping, was born on November 7, 1855, in Chertsey, Québec. This Middletown is situated at the foothills of the Laurentian Mountains near Rawdon, about 30 miles north of Montréal. My grandfather, James Copping, owned and operated a hotel.

Wireless family was still young, my grandfather acquired a piece of property in the area that was to become known as the Copping Homestead. It consisted of 400 acres of fertile farmland and valuable standard of timber. a river, rich in speckled trout, ran through the property.

My father was one of 12 children raised on this homestead. The older ones were fairly well educated but my father never went to school. He was self educated I even talk himself to play the violin. But no problem in mathematics was too difficult for him.

What is his job was to scale all the lumber is father sold and had not been for my fathers knowledge and ability as an estimator my grandfather would never have made the money he did. My father also had the reputation of being one of natures own gentleman, never known to tell a lie. My mother also told me he was good to his parents and a hard worker around his home.

My mother, Caroline Mitchell, was born on November 19, 1857 in Joiners Sq., Manley, Stafford. Before leaving England she was married to one Edward Sliney, Captain of the merchant vessel sailing between Liverpool and Canada. On his lost voyage his ship was wrecked and he was adrift in the open sea for three days. The ordeal proved too much for him. He died of pneumonia.

Later, when my mother came to Canada where are her parents had already settled, she found work selling seeds and plants.

It was the most unusual occupation for a woman in those days and one can only marvel at her pluck, driving alone in her little one horse shay through the lonely countryside in all kinds of weather. I wish I had talked more to my mother about this phase of her life but nobody seem to make much of it. Then one day it was too late.

It was on one of her selling trips that she called at the Copping homestead and met my father. I wish I knew more about this romantic chapter in the story over life but no one seem to make much of it, either. They were married on the 26th day of March 1885, until come house keeping with the rest of the family.

My father inherited the homestead after my grandparents died. My sister Flossie and my brothers James, John, Edwin, and Joseph were born here. So was I, what very cold and wintry night on 18 January in 1890. I was a happy, healthy, baby and had a wonderful childhood on the farm. I especially love the horses I’m Always trying to be with my father when he was working with them. I could watch these wonderful animals in the pasture for hours and I don’t think I have ever seen feels so green or so beautiful.

My father and mother missed my grandparents very much after they died. Mother told me that grandma, though a kind, gentle soul, was also strong as an ox I’m good carry hundred pound sack of flour on her shoulder as well as any man. But grandma also love her we drop and I she grew older often to one we drop too many which made life miserable for grandpa. Despite all this he loved and cherished her to the end.

I never understood why, but my parents became dissatisfied and unhappy with life on the farm. They began to hear things: sounds like a cannon ball rolling across the floor; footsteps coming down the stairs. Pictures fell off the wall for no apparent reason.

My sister Flossie told me that one afternoon after chores she was sitting with mama and papa on the porch, and then suddenly a white clad figure appeared, moving light wind across the fields. It stopped several times and waved, then it disappeared never to be seen again. One night in the middle of winter as we all sat around the big box stove in the kitchen we heard sleigh bells and the snorting and stomping of horses. A man’s voice called “Whoa!” “Who in God’s name could that be?” Papa exclaimed and went to investigate. We all waited and wandered apartment returned alone .” No one was there”, he said in a strained voice. He was very quiet the rest of the evening. When Papa was worried he always took down his fiddle. On this occasion he play louder and faster than usual.

Another time while we were at supper there came a terrific crash from the direction of the woodshed. . Sounds like my woodpile has tumbled down,” papa complained. There were always rows of beech, maple, and birch, all cut, split, and neatly piled up to the roof. He went out to see what had to happened but his woodpile was intact. All he said was, “I think we better move away from this place”, and took down his fiddle again.

But we did not move fast enough. One night soon after the woodpile incident there was a terrible fire and we lost almost everything we owned. We barely escaped with our lives.

There was no place for us to go but to a log cabin in the woods not far away. I don’t know who built it or why it was there but its presence was a godsend. I remember being very happy in the cabin. It was warm and cozy with big bunks to sleep in. Which are passed quickly but I’m sure my mother worked very hard and always with a prayer that very soon we could move to the village where there was a school to attend. Well, with the first spring thaw how are few belongings were packed into Islay off we went to Joliette, at town about 20 miles away.

When we arrived in Joliette a rich cousin who owned a lumber yard took us in. I remember my had been very kind to us. All the children were settled at school and my father was given work as a teamster by wanted his brothers. We moved into a small house close to the mills. We live rent free but my father’s salary was only $5 a week. All my young life I feel bitter about this wondering how the rich Coppings could be so rich and the poor Copping’s so poor. My cousins were always so well-dressed! I envied them

Although I knew it was wrong to do so.

I think my mother must’ve been a wonderful woman, the way she managed on so little. I can still smell her homemade bread, and the pea soup that always seem to be simmering on the back of the stove. She made a big fruitcake at Christmas, too, but I don’t know how. Maybe some of our rich relatives gave her the ingredients for it. And her Christmas pudding! She never neglected to pour a little brandy over-the-top which set off a blaze of colour. I can still see her eyes, right with pride, as they reflected the dancing flames. One of our rich relatives must’ve supplied the brandy, too.

But the rich can also have their problems as I was to realize after my little cousin Nelly fell out of her highchair and injured her back. She was always under the doctors care of the Parish of st. Fish

One day I learned there was to be a “new arrival” at our house. This did not mean to much to me one way or the other, I already had four brothers and a sister. But it lasts the big day came in my little brother Leslie was born. I was allowed to climb up on the bed to see I’m so delighted that I readily gave up my place as a baby in the family.

Then one day my father decided we should leave Joliette. He was very disturbed to learn that the old homestead has been sold. I never really understood what happened. He and my mother planned for many months and finally decided to move to Ottawa, our nation’s capital. I was very happy to be moving to a big city but I do not remember the train trip or even our arrival. I guess I must have slept the whole way. But I do remember looking forward with eager anticipation to my new life and all the advantages city life had to offer. I particularly look forward to attending the big new school and making new friends. All the talk I’ve heard about a new century excited me so I wasn’t quite sure what the talk was all about.

It was 1901. I was 11 years old and my childhood was behind me.

The end of Lilly’s Journal

Lilly McDonald finished school and went on to work in an art studio until she was 23. She married Robert McDonald on February 2, 1914 and bore seven children. She lived most of her adult life in Cornwall, Ontario, just south of Ottawa.