England 1811

The World was quickly changing. The eighteenth century was drawing to a close, the nineteenth century looming into view with for some a promise of better things to come, others foresaw only severe hardships.

The population of London had passed the million mark. People from rural areas were leaving their small towns for the “Big City”. George and Elizabeth were among these new arrivals in London.

Pollution became a concern for many. Crowding in towns and cities created a crisis in the water supply. Poor sanitation practices resulted in contamination and typhoid was rampant. Beer became the beverage of choice and micro-breweries sprang up all over the country.

The invention of the steam engine was altering the workforce. The industrial age was born. Thousands of smokestacks throughout England belched black smoke that settled on nearby roof tops and in peoples’ lungs causing an alarming increase in respiratory ailments as well as other associated health problems.

It was now possible to transport passengers and goods greater distances at greater speeds. Roads were being improved to allow for faster, easier, transport of the manufactured goods to all corners of the island as well as to the seaports. The export trade was greatly enhanced. Stage coaches were also much improved and now carried as many as eight passengers on the new McAdam or hardtop roads with greater speed than had been previously possible.

The turn of the century saw the introduction of a steam locomotive which travelled on rails as well as steam boats that plied the seas without being dependant on fickle winds to carry them along.

Although the ratio was swiftly changing, there were still more people employed in cottage industries than in factories. Records show the years between 1782-1821 to be the period with the worst conditions for the cottage workers.

Those such as lace and stocking weavers worked from their homes. The materials were usually leased from a hosier who supplied the raw material and bought the finished product back. This led to much abuse by the hosier yet the workers had no recourse

The World and its limits was also changing. Science was advancing, with France leading the field. Encouraged by Napoleon, the pursuit of scientific study was rewarded by issuing medals to those who actually published their theories. Despite the ongoing hostilities between England and France, in 1808 a prize for electrochemical studies was awarded to an English citizen, Humphrey Davy. An indication of the importance of this honour is the fact, despite the hostilities, Davy had safe passage to Paris to receive his reward in person.

The term ‘biology’ was coined in 1790 by Jean Baptiste Lamarck who developed a system of classification for the study of biology as well as a theory of adaption.

Pierre Simon Laplace presented his mechanical theory of the universe in 1796.

Joseph Fourier developed the theory of heat and in 1804 Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac went 23,012’ up in a balloon to measure the effects of altitude on terrestrial gravity.

Great strides were also being made in the study of medicine. Leopold Auenbrugger introduced the use of percussion for diagnosing chest and heart ailments and published a report of his findings in 1760. One of his pupils, Réné Théophile Laennec invented the first, rather primitive, stethoscope about 1806 and later published the results of his studies. His work on the thoracic organs, especially the treatise on pneumonia, remained a classic for the next hundred years.

Philip Pinel who was the medical director of the Richelieu Asylum in France in 1792 , was the first person to practice humane methods of treatment for the insane. Pinel tried various approaches to finding a cure for some of the patients. He reduced the blood letting and drugs that were standard treatment at that time, and added a regime of fresh air and exercise rather than incarceration in chains. He printed a paper on his ideals and methods that soon became a standard in the treatment of the mentally ill. The French institute for the mentally ill in Montreal was named for this man.

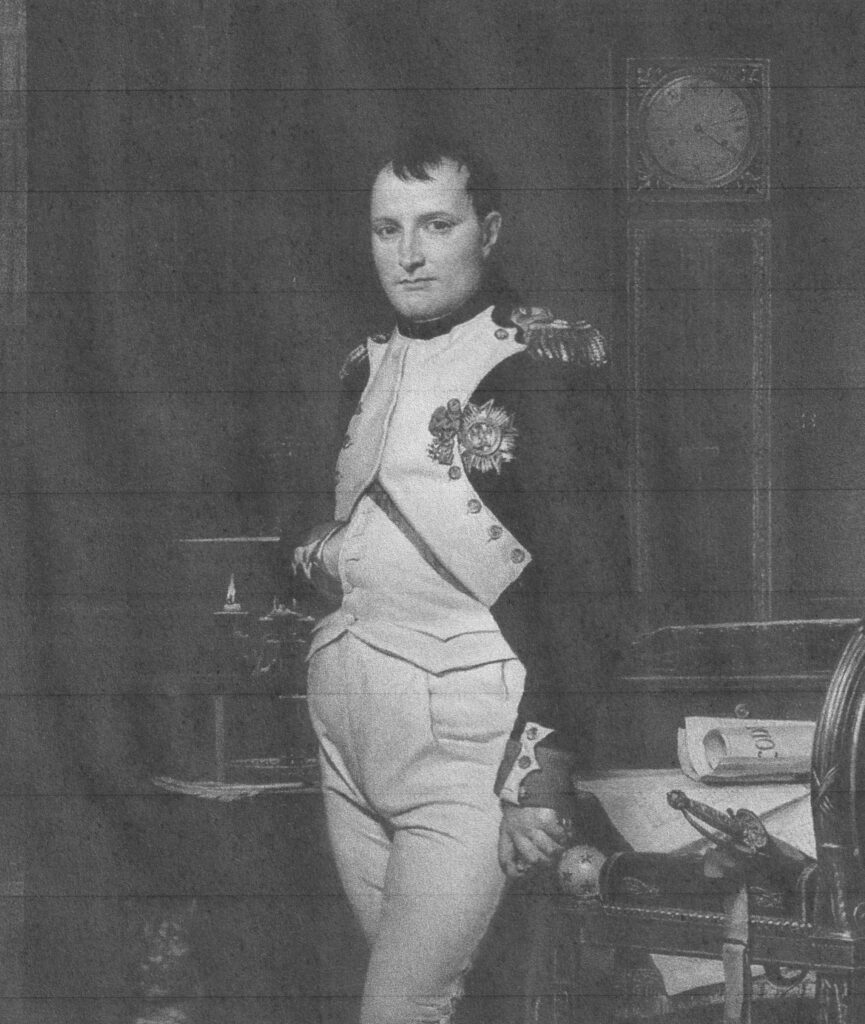

Meanwhile “that dreadful little man” as Napoleon was referred to in England, was waging war throughout Europe.

Napoleon’s rampage disrupted England’s trade with Europe. This had direct and severe consequences on the English economy. Bankruptcies and job losses resulted causing desperate poverty among the tradesmen and working classes. To combat this loss of trade, markets were expanded to the New World and the shipping industry took hold.

To bolster the morale of the English, patriotism was fanned to a frenzy.

Stories were told, poems were written, and ballads sung about the exploits of England’s finest. He might conquer the Continent, but that “little upstart Corsican” was not going to beat the English down!

England, itself, was destitute, many of its people near starvation, but it still held firm against the invader. When Napoleon instituted a blockade, England found the means of supplying its own food. Industry was geared to local consumption. Trade embargoes, bankruptcies, heavy taxes– nothing would make England bow down to his threats.

The navy, with Nelson (1758-1805) as its leader, captured not only the enemy but the imagination and admiration of the whole nation. Like Bonaparte, he was not a big man but what he lacked in stature he made up for in colour. His naval career started at the young age of 12 years old and by the age of twenty he was captain of his ship. He had already served in the Arctic as well as the East and West Indies.

In 1793 when war broke out between England and France it fell to Nelson to blockade the French forces which he did quit successfully.

There were never enough volunteers to man the navy’s ships so “His Majesty’s Press Gang” was sent out to conscript sailors for Nelson’s ships. Men without means were “pressed into service” as well as vagrants and many others unlucky enough to be picked up.

In different battles Nelson first lost an eye, then an arm, but he continued to lead the Royal Navy to victory against France and their ally, Spain. He was promoted to vice-admiral and then made a viscount for his efforts. His final victory in 1805 cost him his life. He was buried with full honours and recognised as a national hero. Today this final victory is still celebrated on Trafalgar Day and monuments to him still stand, notably one in downtown Montreal which has recently been refurbished.

The Treaty of Paris

In the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763, England was given sovereignty over the St Lawrence River. To confirm her presence, and guard against an invasion from the newly found United States England was encouraging settlement in the New World.

Stringent conditions at home also induced many to take to the seas in search of new products and new markets, or even a new and better life in a developing country where land was not only available but relatively cheap. Some were just looking for adventure.

George Heriot, deputy postmaster general of British North America had published a book of his observations in the colonies during his twenty years of service there. ‘Travels in the Canadas’ was published in London in 1807. The publication not only describes the country but gives details on the climate and productions of each area as well as detailing the people and their habitations. It, as well as many other such publications, was meant to stimulate emigration to the Canadas.

Men, such as Heriot, who had personal knowledge of the New World, travelled to the various areas giving talks on the benefits and advantages of emigrating. Might this not have been an influence on George’s decision to go to the New World? A few years later just such an event caught the fancy of the Parr sisters’ husbands, Thomas Traill and John Moody.