Township of Rawdon

The family remained in Montreal until 1821 when once again, despite the advantages in Montreal, George could not resist the temptation to move to greener pastures.

David Petrie and John Eveleigh, who had recently applied for lots in the newly established Township of Rawdon, convinced George that is was a wonderful opportunity and brought him up to Rawdon. George was impressed with what he saw and filed a request for a lot in proximity to Eveleigh’s. In 1820 he was granted a ticket of location, (the first step to acquire land) for lot 24, range 6.

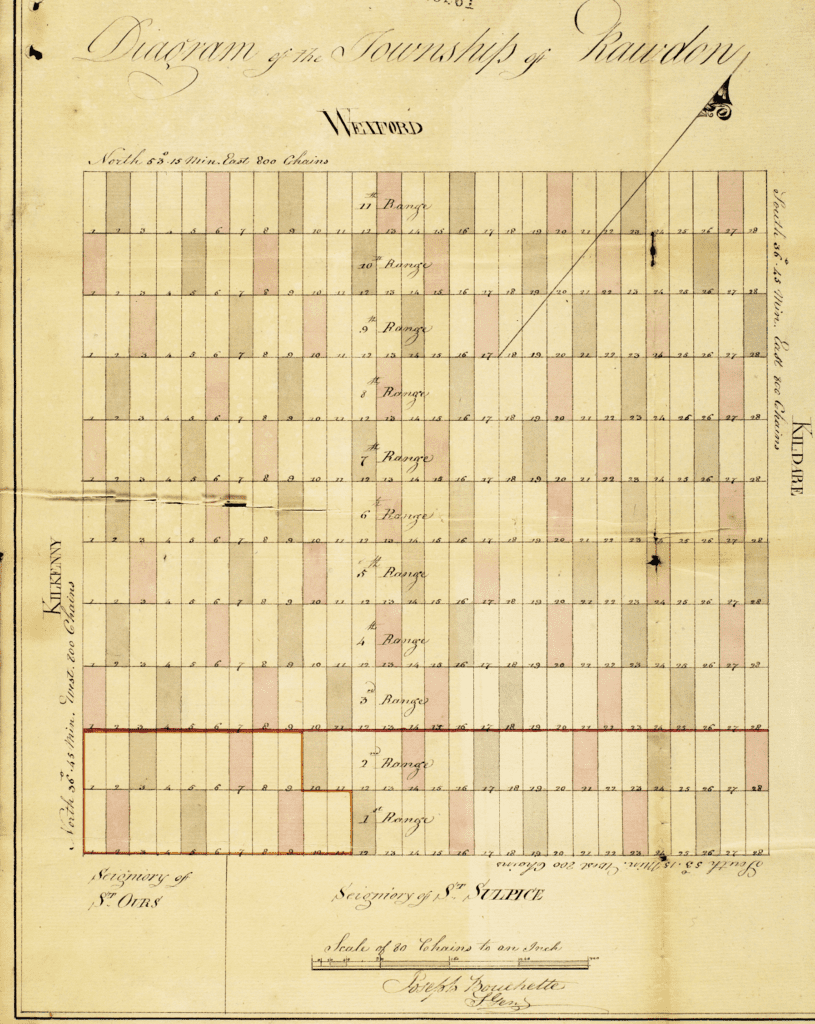

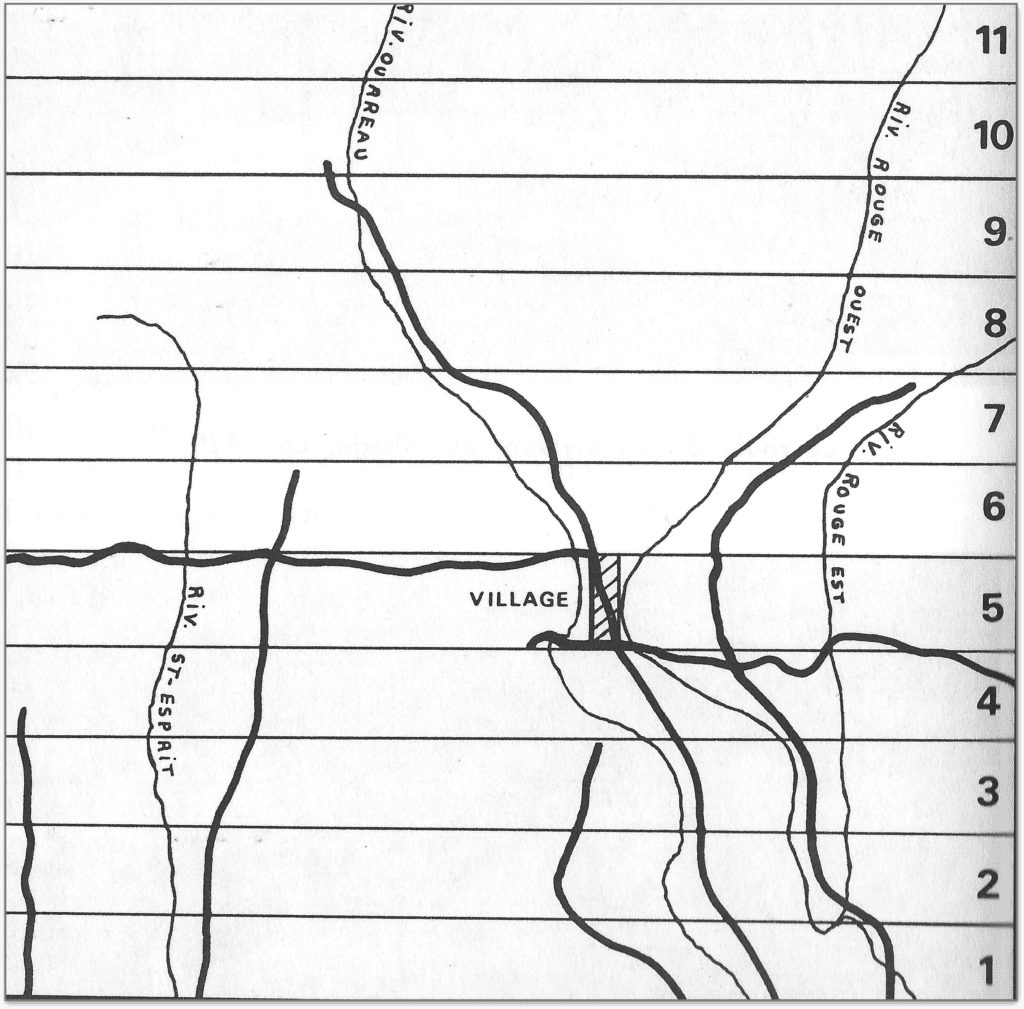

Joseph Bouchette’s 1824 map of the Rawdon Settlement shows the ranges, south to north, 1 – 11 and the lots 1 – 28 , left to right.

In 1798, Richard Holland, a government surveyor, subdivided the first two Ranges of Rawdon into 28 lots of 200 acres each. Rawdon Township was given its patents July 17, 1799, the ninth such patent to be given in Quebec under the English Regime, the 3rd settlement north of the St. Lawrence, to be settled under the English regime. It bordered on the St Sulpice, l’Assomption, and LaChenaye Seigneuries.

In 1815, Joseph Bouchette, Surveyor General of Lower Canada and Lieutenant Colonel, described Rawdon as “having a very uneven surface, rocky in many places, but having good

land in others, suitable for growing grain for profit, and some few even suited to the growing of flax and hemp”. On the higher elevations, the trees were mostly maple, beech and birch with firs growing on the lower spots.

He mentions several streams providing water for the area, as well.

In 1820 there were very few lots surveyed in Rawdon mostly on the 1st 2 ranges.

Parts of Ranges 3 – 8 were surveyed in 1821 and another attempt at surveying was made in 1826 on parts of ranges 2 & 7.

The first lot of grants was issued for the lower ranges about 1821. It was 1845 before the 9th, 10th and 11th ranges were surveyed.

When the Coppings moved to Rawdon Township they embarked on a truly different venture. Their experience in Quebec City and Montreal, both well established towns with all the convenient services could not compare with the reality of the very early days of a settlement.

Such a settlement was totally lacking in services and community organizations such as churches and schools was another game entirely The primitive roads and bridges that could hardly be designated as such limited travel.

What became the final move for the Copping family was a two day journey north east of Montreal the Township of Rawdon. There were now 9 children, the newborn Mary being the youngest, George at 13, the oldest. While eight of the children came to Rawdon, it is believed that Charles, who was about 12 at this time, had been apprenticed to a family friend in the leather trade and did not come to Rawdon.

A 14 mile trek to St Jacques over these virtual tracks, mostly on foot, or with oxen to acquire essential needs was definitely challenging.

Social gatherings with neither church, nor school, was limited. The nearest doctor was also in St Jacques.

Once again the family, with 7 children,(10 year old was apprenticed to a friend and leather merchant, John Eveleigh and remained in Montreal) packed everything up, acquired a wagon and ox and travelled to the east end of the Montreal Island, the first step on the journey to the Rawdon . Here they hired a ferry to cross the back river to the mainland. From there they continued on towards l’Assomption where they spent the night.

At dawn the next morning they continued their trek, (a trek it was as only the youngest rode on the wagon), the others walked, to the Rawdon settlement. At the town of St. Jacques in the Seigneury of St. Sulpice they stopped to purchase basic supplies needed for clearing and building.

Being too late to continue to their destination they camped for the night before facing the last, and most difficult sector of their travel. Once they left the seigneury the roads were more a track than a road imbedded with stumps, roots and rocks. This type of road was possibly the family’s first experience on these primitive tracks.

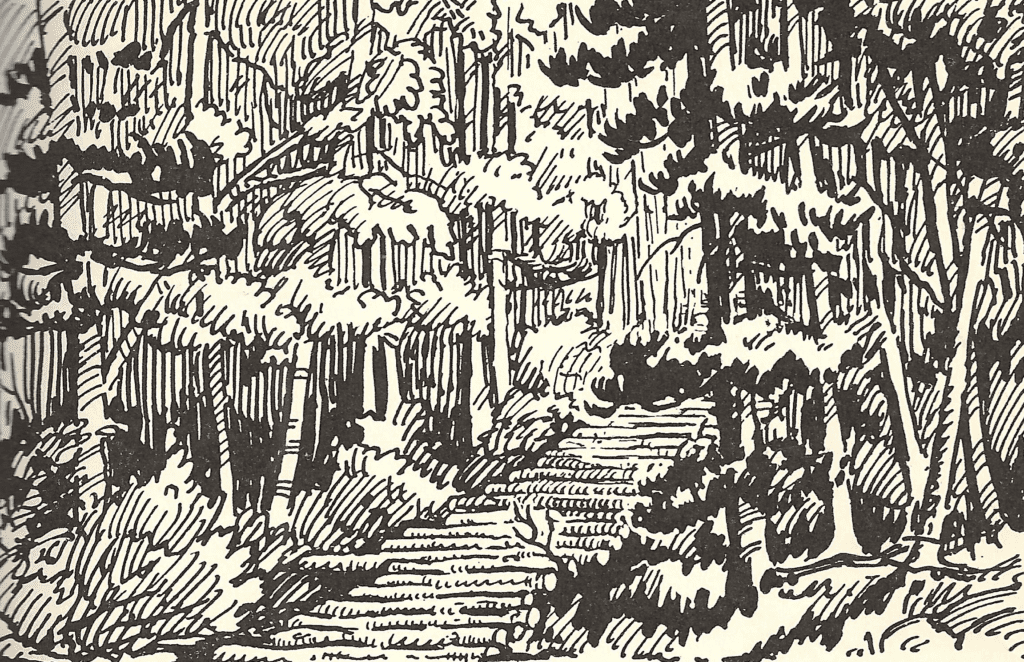

A Corduroy Road

The earliest roads were barely paths chopped through the dense forest. Here, unlike in the forest where stumps were left rather high, trees were cut low enough to allow a wagon to pass over the stump. Rocks that would not impede the passage of a wagon were left in the road while larger boulders were rolled to the edge of the road.

An axe was always fixed to the wagons to chop trees that had fallen into the road or repair damage to the wagon itself.

Boggy or swampy areas, of which there were many, were traversed on a corduroy road. These roads were made of logs laid side-by-side in the mud.

As can be imagined walking on such a road was challenging as clambering over rocks and stumps as well as water holes required a stout heart as well as stout boots.

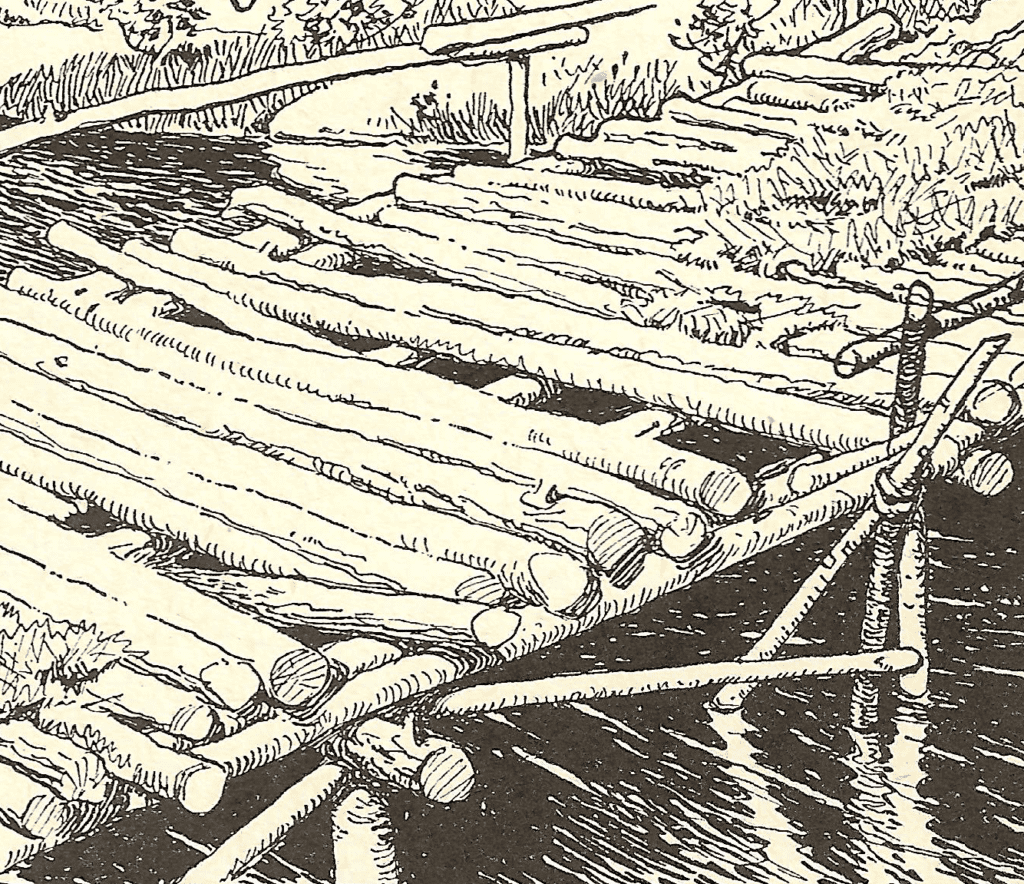

A Corduroy Bridge

Poles or saplings were lain crossways on tree trunks supported by posts driven into the bed of the stream. The cross poles were then covered with moss or earth.

These bridges were always insecure and often dangerous. The poles rotted or broke, leaving gaping holes which could break the leg of an ox, horse, or man if they failed to note the danger.

Heavy rains washed off the earth and high water in spring swept bridges away entirely.

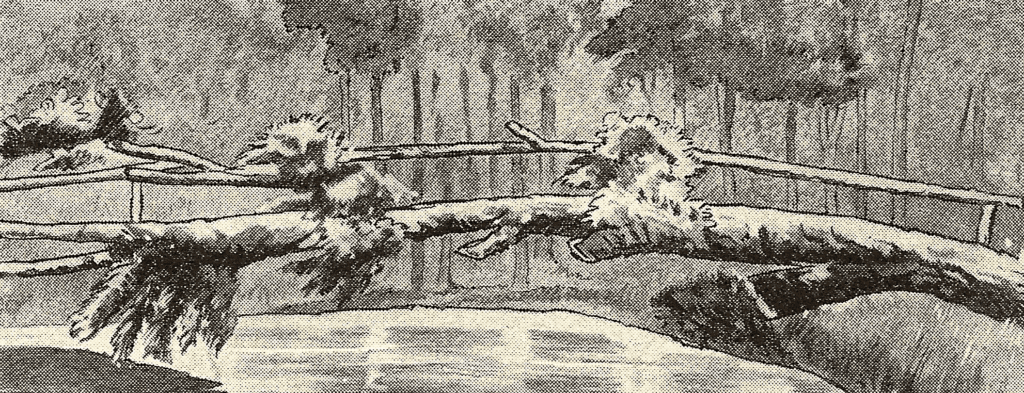

A Primitive Bridge

Smaller streams, where they were shallow enough, were forded. Where the gullies were too steep, or the creeks too deep, falling trees were used as footbridges. Often these footbridges were natural happenings – a tree fallen across the river or stream during a storm. As most travel was on foot these were common sights and often approached with much apprehension.

Larger rivers were crossed by ferries or barges. This service was often offered by a settler on the river to augment his income. Just such a service was offered to cross the Oureau River near what is now 1st Avenue in Rawdon.

This early map shows the roads, some mere tracks, coming into the settlement. They would have entered the Township of Rawdon on the extreme right and made their way up to the 6th range towards riv. Rouge est.(East Red River) passed through their lot.

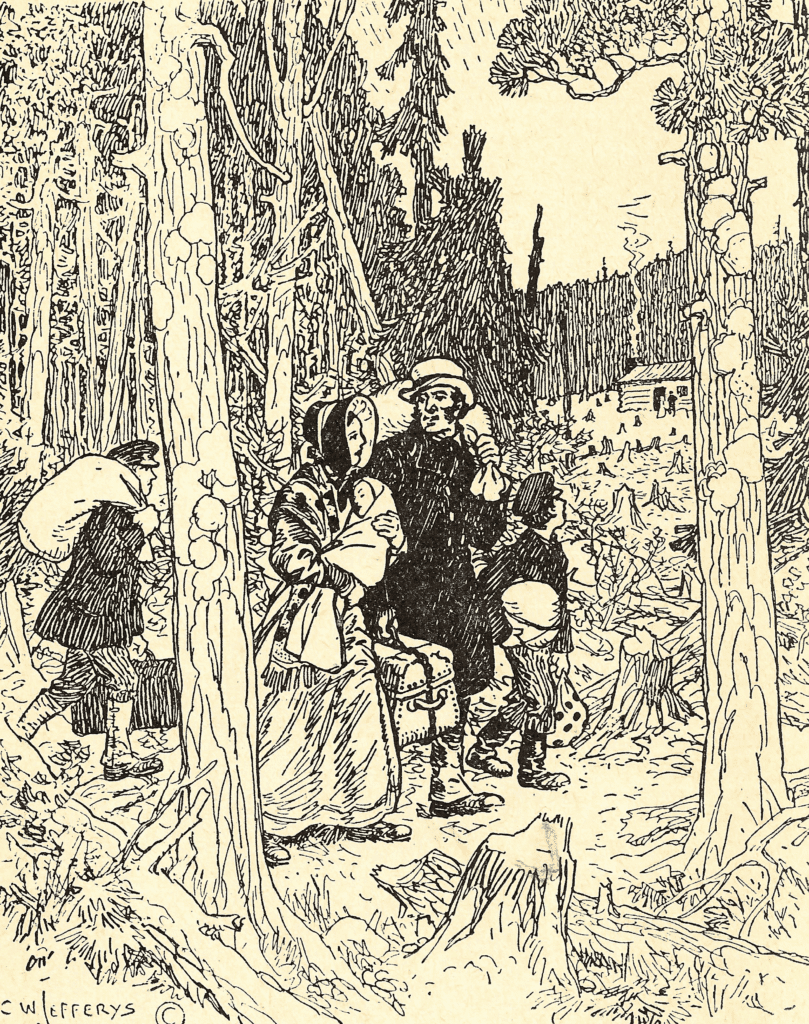

This sketch depicts a family approaching their cabin in a relatively small clearing. The dress was typical of American settlers who arrivedin Rawdon.at time the Copping family came to Rawdon.

Notice they are on foot, carrying their supplies, even the young boys, and the mother has what would appear to be toddler.

Note the stumps strewn throughout. It would be many years before they would have disappeared. It took 7 years to rot a hardwood stump and 25 or 30 to before softwood stumps could be hacked to bits and the roots dislodged.

These eye sores frustrated the ladies, particularly. Usually limited to an area close to their cabins they became very tired of looking at rotting stumps. It was virtually impossible to make the outdoors look tidy with stumps thrusting their ugly heads all about.

A closer look at an early cabin. Note the rocks piled to the left of the cabin. Rocks were plentiful in Rawdon Township and a bane to cultivating the land. Every spring, even twenty years after their arrival, the Coppings hitched an ox to a stone boat (a low sledge) and picked rocks from their fields. In one area towards the 11th range it was said that what grew best in the fields were rocks.

This clinging lady certainly does not reflect Elizabeth nor her girls who trod the roads and worked in the fields as well as their brothers.

On the way to the Township an overnight stop was made in the town of St. Jacques to gather supplies to clear, build and nourish the family. This little, but well established, village 14 miles from their lot in the Township would be the commercial centre for the Coppings.

A careful list of the requirements was made before gathering the necessary tools and equipment that would be needed in their new location. This included a spade, an adze, a felling axe, a brush (bill) hook, a reaping hook, a pitch fork, pick axe, scythe, two hoes, a hammer, a plane, chisels, an auger, a hand saw, two files, etc. required for clearing and tilling the land. George always liked to be well equipped for the task at hand so the basic tools were supplemented with a pit-saw, a grindstone, a crow bar, a sledge hammer. This was quite a collection to be hauled on a travailand carted to their lot on the 6th range.

With a mind to having to build a house as soon as possible there was also a draw knife, a pair of hinges, a door, nine panes of glass, 1 lb. of putty, 14 lbs. of nails.

Once they left the seigneury the road became hardly more than a trail blazed through the bush allowing only oxen or horses with travails to pass. From Montreal the road had been mostly on flat land. At the limits of the Rawdon Township hills, leading to the mountains, rose up before them. Spreading roots, low hanging branches, and rocks challenged the progress of the travellers and their luggage along this very rough hewn road.

The Copping Family

1821

George Copping age 39

Elizabeth Mallion Copping age 38

George William age 14 years

William George age 13 years

John Charles age 11 years

Clarinda age 9 years

James age 7 years

Thomas Henry age 5 years

Henry Thomas age 3 years

Mary newborn

This is the family who arrived in Rawdon. Mary born September 20, 1821 was probably born soon after their arrival and was baptized in Rawdon. Note Elizabeth’s age, 38, yet she went on to give birth to two more children, rather unusual for that time.

George would not be considered in his prime, either. He did have 2 boys, George and William, of an age to be considered men. John was apprenticed shortly after their arrival, to Philemon Dugas’ mill.

The first task was to create a temporary shelter to protect the family until the fall when, hopefully, their cabin would be ready.

Once this was done an area lage enough to build a small log dwelling was cleared.

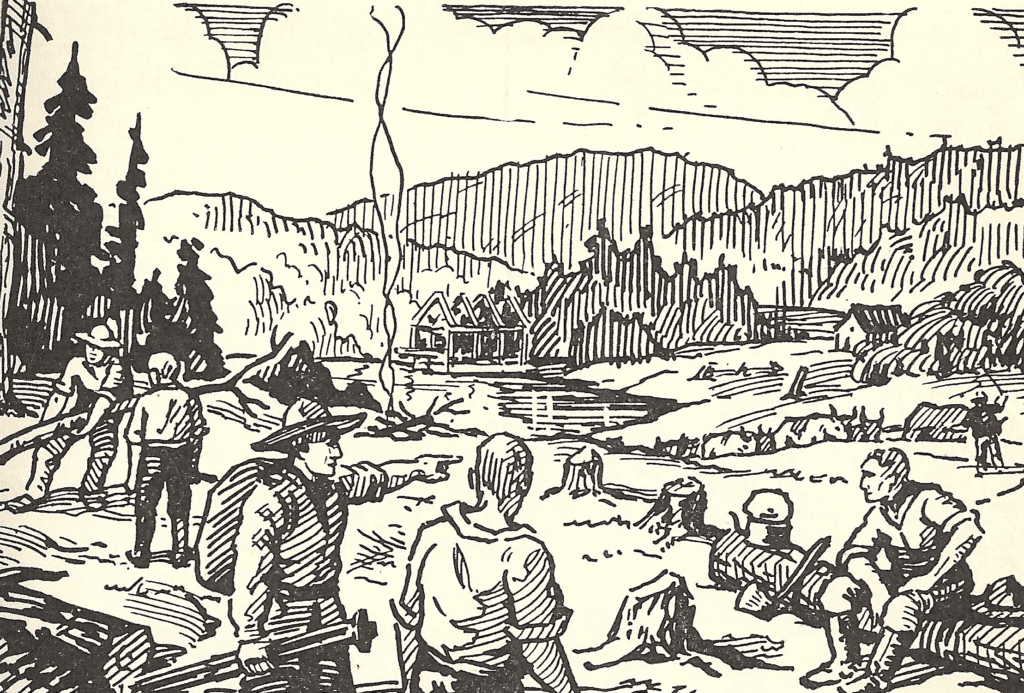

Bees were very common, sometimes two or three were held in the same week. Bees were a more practical approach to work that was very labour intensive. Newly arrived settlers, such as the Coppings, could gain much experience working with seasoned hewers.

The ladies served meals for the workers, usually dinner and supper. Tea and possibly beer or whiskey was served to the men at the meals. Although the ladies did not usually accompany their men to a bee, they frequently sent contributions for the meals. In the evening the ladies and children might join the party for dance and song, and keep an eye on their men that they did not drink too much alcohol. Sometimes a little too much spirits resulted in tragedy such as the killing of Robert Brown.

The Coppings, in fact very few settlers, very seldom worked alone whether it was logging, making potash, or in the fields ploughing, planting or harvesting. In return they spent many days working at a neighbour’s farm or in the bush.

As the Copping boys grew older they attended the bees while George stayed at home to tend to business and community interests as well as seeing to the animals and working on the farm. If the bee was held at a near neighbour or close friend, he and Elizabeth joined in the evening festivities.

Building a Home

George and his boys, George, William, and John, chopped and burnt every day through spring into summer. Finally there was adequate space to build as well as the logs to build a cabin.

A cellar had been be dug out and lined with small logs to store their potatoes and all other such provisions during the winter. The house was erected over this space.

A bee made good work of getting the walls of the house up and a start on the roof made.

Holes were then cut in the walls for a door and a window. To conserve heat usually only one window was in a cabin.

The gables were boarded and the shingling began.

Elizabeth waited with great anticipation for the completion of the cabin.

At the end of summer, while he house was not completely finished, the family moved in.

They had a roof over their heads once again!

Before the frost came, the outside of the house was banked with earth to about a foot high around the foundation. This was done to protect the cellar from frost and limit cold drafts blowing through the house during the winter.

The family lived and expanded in this dwelling for the next fifteen years.

Elizabeth, Clarinda and James set about winterizing the cabin. The walls had to be carefully examined and any holes chinked with a mixture of moss, clay, and lime.

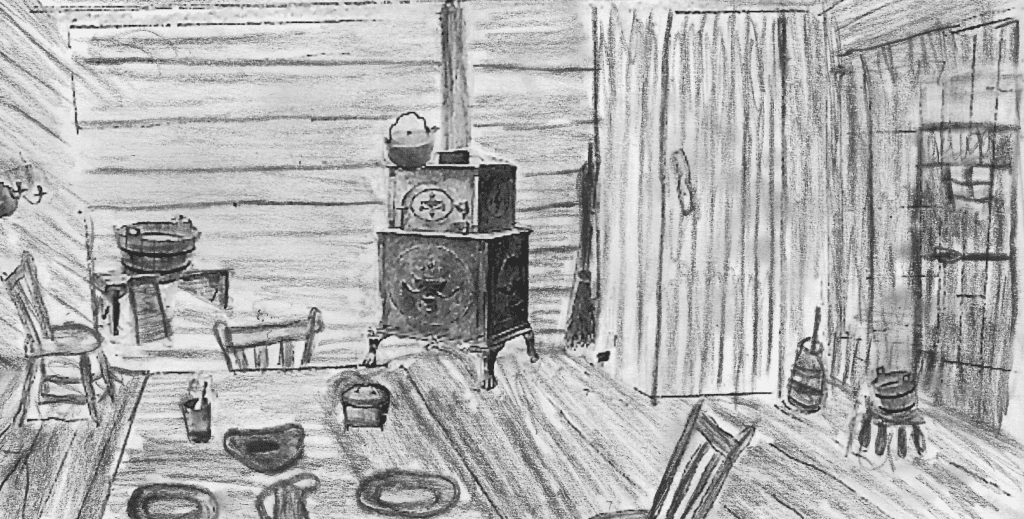

When the first snow arrived it would be shovelled against the sides of the cabin to help retain the heat from the one stove that provided both a cooking surface and heated the home.

Despite their efforts, during the coldest winter days, the temperature in the cabin fell well below freezing temperatures. The ladies suffered from chapped hands and cracked fingertips. A bit of

lard rubbed well into the hands helped relieve the condition. In later years, when there was

wool to spin, the lanolin provided some lubrication for their hands but the first winter there was no wool to spin or knit.

The cabin was completed but for George and the boys, there was still plenty work to be done before winter. A stable was needed for the oxen, a cow, the pig, a couple sheep, chickens and geese. For the first year what little fodder could be garnered for winter feed was stored in a lean-to.

Supplies for the family had to be purchased this first season as there was no garden to supply vegetables nor animals for meat. Preserving food was a challenge as there was as yet no cellar in the house. Vegetables were stored in a large, sturdy, wooden box just outside the door. Meat was salted and kept in a barrel. Once the temperatures went below freezing, fresh meat could replace the salted fare.

When all was ready in the home and barn yard, George and his sons, George and William, went back to clearing land for spring planting.

George was always looking to make a profit and having worked in a large saw mill operation in Quebec City area, he was familiar with the various types of trees and the value of the different logs. He knew beech, maple, and hickory made good firewood and that it took many cords to heat the house during a long, cold, winter.